Must See TV

My first encounter with therapy was in 1979 when my husband and I went to what was called couple’s counseling. We were five and a half years into our marriage and a year or so away from turning 30. The appointment was my idea. After a couple of visits from the two of us, the therapist, a man, invited me to come by myself the next time.

“Sure,” I responded, wondering but surely on some level knowing this had to do with my proclivity, of which I did not (could not) call its name — lesbian. A much maligned unit of the English language kicked about in the culture I grew up in, lesbian was considered a dirty word, a member of the lexicon that when uttered or blurted out by children led to their mouths being washed with soap.

So you can imagine it would take time for me to get used to hearing “lesbian” roll off my tongue trippingly. So until that time would come I knew myself by the label “tomboy”, even as a young professional woman. Go figure!

I actually thought it was a good idea to have a one-on-one with the marriage counselor, whether I was able to articulate what was happening or not. My thoughts and considerations had me moving out of my marriage and into something very different involving women and my relationship with them. I was seeking the therapist’s take.

At this stage, I had already made out with two different lesbians who felt the call to tutor me in the kissing department. In turn, that drove me to proclaim my love to a straight woman on my softball team: a whim drove me to her apartment unannounced and smitten. After the love word and before I had the chance to follow up with a second word or two and maybe a kiss, she lost all color in her face and escorted me to the door. We didn’t socialize much after that.

And I told no one the story until many, many years later. Gender roles at the time were strictly defined in hetero terms, and defying them often preceded loss — jobs and family for example. And remember, I was still in that high profile TV reporter job of mine.

From the get-go, I had no interest in bringing this background information to the counseling couch. It was a trust issue, not wanting to expose myself to the therapist, but it was clear soon enough that he had little interest in the details. I would soon learn he chose his words carefully for this particular situation, bypassing a host of descriptives — lesbian, gay, homosexual — that probably fit the bill better.

A few weeks later, I walked into his office for our first solo visit. We had a chat that began with me watching the marriage counselor turn his gaze to the third floor window that overlooked a tennis court in the park across the street.

A lone, random man was practicing his serves. “The fellow batting the tennis ball around, you see him?” the counselor asked me. He and I both had been pausing our words and glimpsing every so often at the tennis guy as we exchanged thoughts and observations, a convenient distraction when the only other option was to make eye contact.

“I do see him. Uh, huh. Yes.” I was not a big tennis fan. And, of course, that’s not what the therapist wanted to discuss.

“Does it turn you on to check out his butt? Are you attracted?” He kept his eyes on the tennis fellow for a few beats, then turned to me. I looked at the guy’s butt.

“Hmmmmm.” I was feeling a bit uncomfortable about the fact that I was not getting turned on by the dude’s behind and might have to talk about it. Then I considered my husband, thinking that if I thought specifically about him I would feel a little something that would allow me to pivot back to the therapist with a simple, “Well, maybe.” But that did not happen.

Then I considered all men. “No, not really,” I said to the therapist, who was watching my body language and jotting down notes.

My lips had uttered the truth – and, wow, it was a big revelation for me, never thought about a lack of attraction to men. Because why? The strictly structured culture I was immersed in did not provide options. Until it did — when my true nature revealed itself in the few make-out sessions I had with each of those two lesbians bent on tutoring me with lingering kisses that stopped time.

The therapist’s smooth segue into the heart of the matter came next. But let’s just slow down for a minute or two before we get to the therapist’s suggestion.

It’s interesting to me that several years before this visit with the marriage counselor, one of my television news stories predicted my coming out as a lesbian. Not only that, the visual content of the story paralleled my experience on the therapist’s couch, particularly his question, “Does his butt turn you on?”

Reviewing this television clip 35 years after the fact, I can so easily read between the lines. Mixed with the touch of sarcasm in my words and tenor, my body language seems to clearly signal that I am not interested in men’s boring bodies, no buts about it.

Now that’s a TV reporter with a sassiness written all over her face as she lingers on the corner watching if any gals go by. She has at least two years before she steps out of her closet.

My intention at the time I wrote and reported this story was to present one response women had to the second-wave feminist movement sweeping through the decade of the 1970s. I think the story’s covert meaning was lost on most everyone except the two lesbians who instructed me in the art of kissing a woman.

But back to the therapist, whose smooth move from my lack of enthusiasm towards a man’s butt cheeks transitioned the conversation to the heart of the matter.

“Do you know what androgyny is?” he asked me. That was as close as he was going to get, given the touchy nature of the topic of homosexuality at that time in the culture and society.

“Well, I kind of know,” I said. That’s what you say when you don’t remember ever looking up a word and not a clue is making itself known to you in that moment.

Of course, I knew what he was getting at, but wanted information directly from him, which he offered tidbits of. I was glad the counselor, whose name escapes me now, never talked about sex, comfortably pinning everything on mens’ butts. But he did offer a simple, declarative sentence that got my attention.

“I have a book that might interest you.” He held up a hardback titled something like Recognition of Androgyny. The cover of the book was unassuming, brownish in color, the title was black, the typeface block.

Androgyny describes someone who possesses traits of masculinity or femininity that contradict their birth gender. I’m a good example of a girl born with girl parts who had what were considered boy traits, hence the word tomboy, used to describe gender-mixing girls like me.

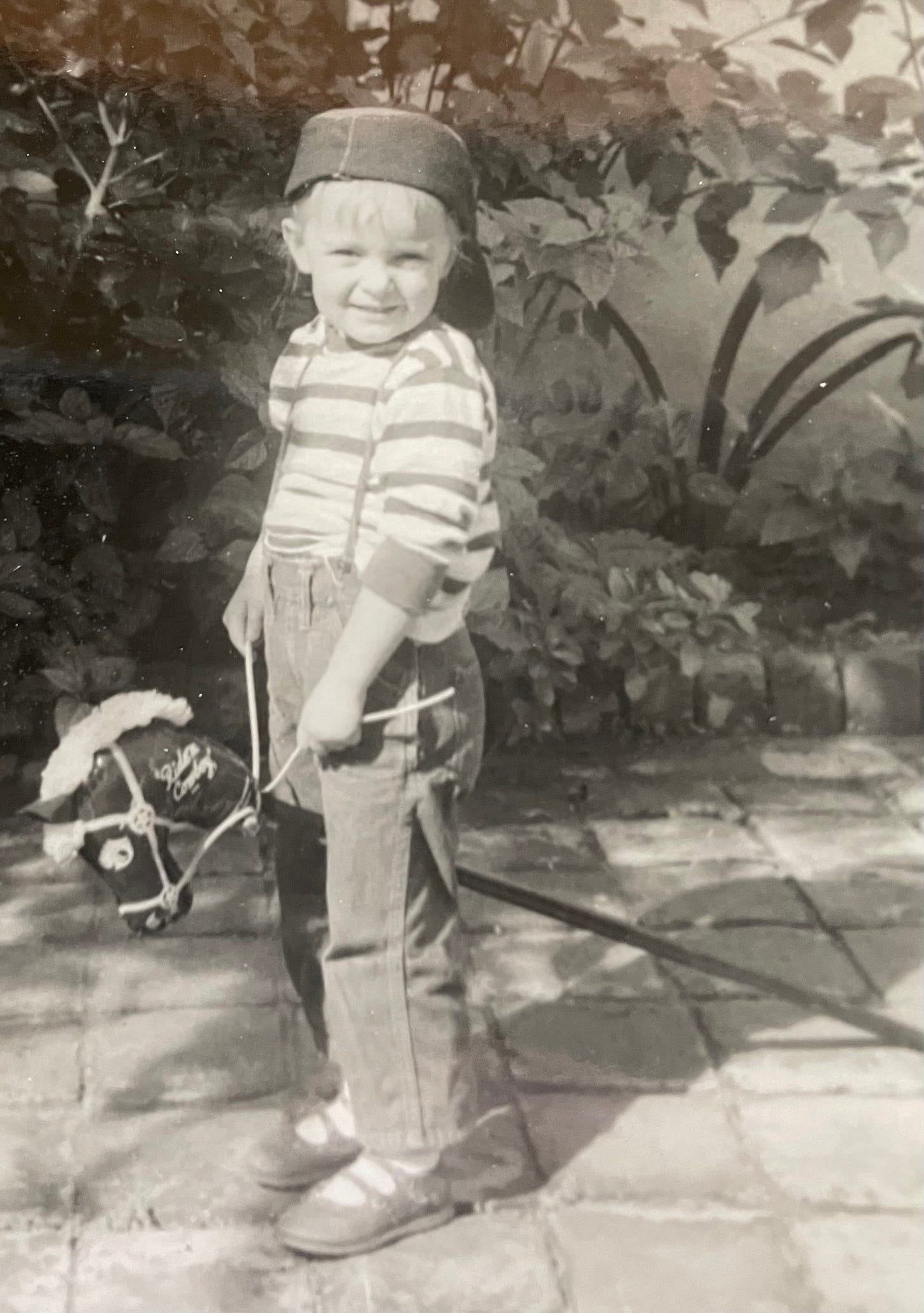

Here’s me in my early androgenously tomboy years, in the neighborhood of three and a half. The Mary Jane shoes provide a lovely contradiction.

Historical records tell us the definition of “tomboy” has remained pretty much the same through a multitude of centuries, all the way back to 1550 or so. No kidding. The word describes, more or less, “a wild and romping girl who acts like a spirited boy,” a label that contributes to just one of many secrets, contradictions and lies which confuse our notion of gender and sexuality.

“Yes,” I said, genuinely interested in the book’s topic. “Where can I get a copy?” I was looking forward to finding information and/or answers in the book that I was wishing and hoping would guide me along this path I was on with no interest at all in turning around and going back to where I had come from.

The counselor flipped through the book’s pages randomly, probably checking to see what marks or comments he may have scribbled in the margins and might not have wanted to share with me. The pages passed muster and the marriage therapist handed the book to me.

“I’m happy to loan it to you.”

I said thank you and reached for the book. I read it most of it a short time later while sitting in the passenger seat while my husband drove us in his forest green Ford Maverick from Dallas to Salina, Kansas, for my ten-year high school reunion. On the return trip I finished the book and it was only a matter of months before we were no longer legally wed.

As soon as my husband and I verbally agreed to the divorce in late summer of 1979 I took clothes and other personal items from the house and moved in with one of my lesbian tutors.

While the decision to divorce was mutual and conflict free, I do remember that after moving in with my new gal my husband made an unannounced visit to her home one weekend afternoon and asked if I might reconsider. The divorce was due to be finalized soon.

We spoke briefly. I said no, that it was clear to me I needed to leave our marriage and find my way along this fork in the road I was taking. We parted ways. I stayed in Dallas, my ex moved to Houston for a newspaper job there.

Way too many years passed before I sat down and crafted a hand-written letter to the man I married mere months after we both graduated from Southern Methodist University, both with a Bachelor’s Degree of Fine Arts in Journalism. We had a short, but rich history together, including lots of love, much respect for the other and a shared dedication to protecting freedom of the press and democracy.

Elements of the letter I eventually wrote, the sentiment I wanted to convey or not convey crept into my thoughts over the years — teasing, taunting, nudging me. Those years after our parting I wrestled with regret about the way I behaved, conversations I never had, the times I stepped out towards the end there. I was not completely honest on occasions which needed truth telling. All that stuff was for me to wrestle with and learn from.

“I wish I had been more graceful in my leave-taking,” I wrote in the letter to this special man in my life.

….. to be continued

That's an absolutely lovely story and I think you were very brave - at 30 - to leave what seemed like a perfectly good man and marriage and leap into a world barely known by "polite" society. You had no idea, really, if it would ruin your career. But you recognized the truth in yourself. And I think recognizing truth is what journalists do best!

Yes, I did recognize my truth. The man I was married to also recognized my truth, which is the greatest gift of all.