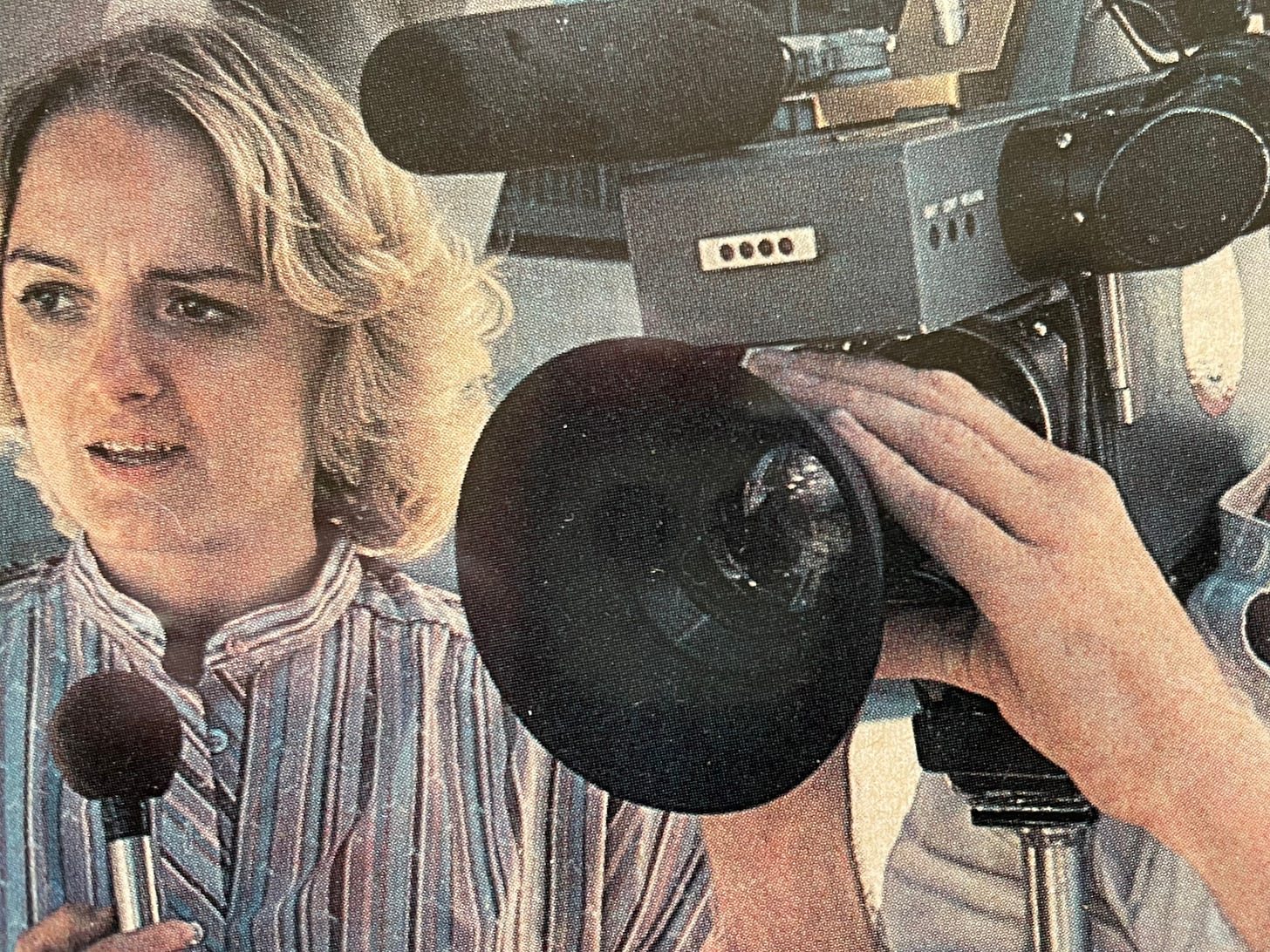

There I am at the top of my game – from Sapphic softball to Carmen's mentoring, to investigative reporting – after finding my voice both literally and figuratively, divorcing my husband, and moving in with my first lesbian lover. Life was good. What follows is the final chapter of the prelude to my busting out of the closet and going public – proclaiming myself a lesbian.

__________________

It was the mentoring from my television news colleague Carmen during the beginnings of my on-air reporting that revved my journalistic engine. She gave me permission to be more assertive and audacious, to challenge the patriarchy loudly – prompting me to put myself firmly on a trajectory to crack the proverbial glass ceiling. Bold and competitive in my reporting, I gave the uber masculine male reporters a run for their money.

I was an anomaly in the burgeoning local television news business but didn’t really get that – except in retrospect. At the time, I saw myself as a focused young woman out to prove herself in a man’s world, in addition, I was intent on further discovery of my newly remade personal life.

By 1978, I had divorced my husband and moved in with a gal who worked as a head nurse in the emergency room at Parkland Hospital, Dallas County’s public medical facility. We’ll call her Sara. She was the one who opened a window to let in refreshing air for me to breathe – lesbian tent-camping trips in the woods, bare-breasted canoeing on the Guadalupe River in the Texas Hill Country, six canoes, each filled with two lesbians. I was enlivened.

Sara also introduced me to lesbian music – cryptically referred to in public as “women’s music,” the lyrics of which lent clarity to the Sapphic flavor of my transition to a full-on lesbian.

For example, Chris Williamson’s iconic album, The Changer and The Changed, featured classic, gentle folk-rock songs — “Waterfall,” “Sweet Woman,” “Song of the Soul,” “Shooting Star.” Soaked in women’s love for each other, the lyrics also had a spiritual goddess-ness mixed in. In the 1970s, this genre of music called out to young women like me who were slowly, and perhaps perplexingly, or without a clue, emerging from the closet, claiming their souls, finding their voices – the essence of who they were — then finding themselves under the magic spell of sex — ahhh! — with a woman.

The songs’ lyrics spoke to an eager place in me that wanted to bust out of the closet and get real. Lots of us elder lesbians probably still remember enough words to these songs to sing along with confidence. In absorbing their lyrics and feeling the music, we were searching for our voices. I know I was – with Sara as my teacher.

One weekend evening, after a couple of beers each, Sara made an announcement. “I think it’s time,” she said, embracing no particular context.

“Time for what?” I was engaged, an eager learner. My girlfriend stood up from the sofa and walked over to the stereo, flipped through a stack of albums leaning against the wall. Each album contained a 33 RPM vinyl record.

I was sitting on the sofa, stretching to see the cover of the album and the musician’s name. Sara pulled the vinyl from the album cover and set it on the turntable. “It’s time for you to hear this song.”

“Come on, tell me why,” I pleaded. “What’s the name of it? Maybe just a tiny clue.”

“Just listen,” she said, taking a quick sip from the Lone Star beer bottle she was holding. The usual lyrics in lesbian music were filled with metaphors and vagueness. Chris Williamson’s hugely popular “Waterfall” is a great example. But the song Sara played for me because she thought I was “ready” did not mince words. It was Meg Christian’s song, Ode to a Gym Teacher. Here’s the refrain:

She was a big tough woman, the first to come along

That showed me being female meant you still could be strong.

And though graduation meant that we had to part,

She’ll always be a player on the ball field of my heart.

“Oh, my god! That’s great.” I said. I was smiling and simultaneously understanding the truth about my seventh-grade gym teacher. Sara’s eyes lit up. “Figured you’d like that song. It resonates.”

I then launched into my gym teacher story for Sara to hear, but will leave those details for a later story I’ll be writing, and probably not with the details you might assume.

During the three or so years I lived with Sara, she taught me all about lesbian culture, such as using the coded term “sings in the choir” to describe a person who was lesbian or gay. You could say it like this: “Trust me, that gal across the way sure enough sings in the choir.” Sara also introduced me to the lovely, intimate sexual side of what it was to be a lesbian, thank you very much.

Now to the newsroom at WFAA-TV where I'd cranked out many a story that kicked butt – calling out politicians’ misdoings with taxpayer money and businesses that refused to serve Black customers. Then I took on a new beat – reporting on the Dallas school district, which allowed me to ramp up from my work covering the Dallas County Commissioners Court.

The time had come to apply all of my journalistic skills to a new arena where I could play hardball. No more softball stories about misspent taxpayer money on new carpet for a county commissioner’s office. This time, I would ferret out a wealth of graft and corruption involving federal monies earmarked for desegregation projects.

But then, the unspeakable – literally. My television news voice left me suddenly, without notice. Nurse Sara suggested I just let it run its course – whatever the cause. But I could not sit idly by and wait for the absconded voice to return on its own time. My doctor could not figure out what caused my voice to go gravelly and raspy. The first and only time I visited him, he seemed a bit perplexed.

“Okay, Kay. Here’s what we’ve discovered in your throat – no irritation, no trace of laryngitis, nothing out of the ordinary that might cause you to lose your voice.” The doctor pulled out a script pad from the front pocket of his standard white coat and made some scribbles.

Looking up from the pad, he offered his solution. “Here you go, a prescription for a little extra help in your recovery.” He prescribed a routine of steroids to spray in my throat every morning for a week or so. Turned out the steroids didn’t do much to bring my voice out of hiding, leaving me helpless — and voiceless — when it came time to record the voice track for my stories.

Since there was nothing amiss about the rest of my body’s health, I dutifully kept reporting to work. But for someone whose job is to appear on camera and talk into a microphone, having their voice go missing makes things tricky. I was rockin’ at my job and didn’t want anything to get in the way of my upward trajectory, so I kept on keepin’ on, duty bound to at least fracture the proverbial ceiling of glass with grit. At the time, I didn’t realize that was exactly what I was doing as an investigative television news reporter who just happened to be a woman. Such a thing was virtually non-existent at the time and I was helping pave the way for those women who came after me.

In order to keep my daily news reports on the air, I came up with a plan to continue ferreting out daily stories at the school district – gathering information, conducting interviews, writing scripts, etc. – then turning over my written words and the narration to a kind colleague who agreed to loan their voice to my stories and still give me credit for the work I had done. This band-aid was not sustainable, however. Plus, my voice wasn’t getting better and there was very little steroid spray left. I was swimming in anxiety for fear of losing my prized education beat to another reporter. The newsroom at WFAA was highly competitive, driven by “creative tension” – our news director’s description of his somewhat cutthroat leadership orthodoxy.

The loss of my voice was perplexing and concerning. Angst nagged at me. How long would this last? Over and over, I wrestled with this question that had no answer, except, “hard to say.”

“Hey, Kay. Come over here for a minute, would ya?” The producer of the six o’clock news, a fellow named Sparky, summoned me in his soft Texas drawl, probably wanting to know how my story was coming along. I nodded acknowledgement in his direction and began walking across the expanse of the newsroom, filled with metal desks scattered about with enough space for a couple folks to walk sort of side by side.

“Hi, Sparky,” I rasped as I walked up to his desk. Speaking slowly and quietly (but as loud as I could muster), I gave him the bad news. “I’m not sure I can get this story done for today.”

It was late morning, and Sparky was expecting my story for the six o’clock news, a piece about the school board denying a pay raise teachers had been promised, then blaming the superintendent for the crisis.

“I’m having a hard time getting an interview with Superintendent Estes and we still have to shoot B-roll.” My soft gravelly words gave away my weariness, making it clear I was frustrated. At the time, I was not one to smile much in the newsroom. I took my work very seriously, leaving little room for joking around.

Sparky looked up from his typewriter and replied – in a fast and firm staccato. “Kay, I’ve got to have that story. I don’t have anything to fill the slot. Do we really need that interview from Estes? Find somebody else if you have to.”

Having expected that reply, I moved on to an fyi. “Sparky, another thing. My voice is still not doing well, as you can hear. I’m going to have to get someone else – again – to do the voice over for the story.” This switcheroo had been trending since the beginning of the week – just one more irritant in the daily rhythm of the news cycle. I could tell Sparky was full up with irritation, just like me.

“Whatever you have to do, Kay, just get it done.” Sparky turned his head towards his IBM selectric typewriter and fixed his attention on finishing a script he’d been writing for the noon show when I approached. The newsroom was never not bustling and almost always thrumming with our news director’s favorite energy – “creative tension.”

Prior to the leave-taking of my voice, I had begun researching federal monies made available to the Dallas Independent School District during the early 1970s for desegregation projects. The monies were earmarked to renovate an abandoned shopping center into a high school. I’d been going through several file folders stuffed with invoices, receipts, and payroll lists submitted to the school district by the Maxwell Construction Company. Later down the road, my research revealed the company was overcharging taxpayers with padded payrolls, and double billing the district – a crime the feds would later become very interested in.

Hoping desperately that my voice would come back sooner rather than later, I decided to approach the news director, Marty Hagg, with yet another “temporary solution” until my absent voice returned. The door to his office was cracked open when I knocked once and walked in unannounced – a standard practice that spoke to the vibe of the newsroom, action central. Marty was watching a round of stories from a reporter in a small TV market who wanted to move into the big time. Larger cities like Dallas were the usual stepping stones into one of the three major networks – ABC, NBC, and CBS.

The news director’s recently renovated glass-walled office, with its wall-to-wall dark coffee shag carpeting, offered a panoramic view of the newsroom and its goings-on. This made it easy for Marty to keep an eye on things – reporters thumbing through notebooks, pecking on electric typewriter keyboards, and photographers hauling their camera gear towards the nearest doorway, hightailing it to a five-alarm fire or a shooting at a 7-11, or whatever piece of spot news had blared from the police scanners sitting on the assignment editor’s desk.

“Hi, Marty. Got a minute?” I croaked.

“Sure.” His voice was nasal, often marked with pauses, as if he was thinking. He looked up at me, peering over the glasses perched on his nose. His beard was full, with sprays of gray. This day, he was wearing a soft blue dress shirt with a white collar. As usual, his tie was loosened and sleeves were rolled up, just above his wrists – a tradition among men, suggesting a readiness to get to work.

I had a nervous stomach and most likely was wearing a skirt and some sort of blouse – the skirt was part of the wardrobe I would ditch when I morphed from straight reporter to lesbian activist. I would, however, keep the rolled up sleeves look. At the time it was unusual to see a woman sporting that stylish detail – for me the gesture set me apart from the traditional woman and provided an air of confidence. My long, straight hair from the early days of my TV career was shorter at this point – wavy thanks to a permanent and punctuated with blonde highlights. Once TV news was in my rearview mirror, my hair got shorter and butchy in a 1980s mullet kind of way.

I maintained eye contact with Marty and cleared my throat, hoping my voice would come out strong enough to be heard. “This deal with me writing and producing stories for other reporters to voice over is not working.” My voice sounded soft and raspy, even after a quick spray of what remained of the steroids before walking over to his office. I cleared my throat again. I stepped in closer to Marty’s desk. “I’m finding some good stuff at the school district. Misspent taxpayer money. Graft and corruption stuff.” I was doing everything I could to secure my place as an investigative reporter. It turns out there’s a chance I was the first woman in the country to be an investigative reporter for a local television news station. Marty understood this but never revealed it to me.

Given Marty’s joie de vivre over his reporters competing with one another for the best stories, I stood before him anxious that he might pass me over if I didn’t produce something big soon. But I kept my edgy self in check, as my mentor Carmen had taught me, and brought him a proposal I figured would keep me in his good graces.

At the time, the luxury of having room in the workday for research in the TV news world was a rarity. Television news was a slam, bam, thank you ma’am collection of happenings bundled into a 29-minute container Monday through Friday at six and ten in the evening, the bundle filled with chatty news, weather, and sports anchors, plus video packages of news events, each of which averaged a minute and thirty seconds in length. Pulling stories together, often within a single day, or just several hours, left very little room for deeper thought or research in the dawning days of local television news. It was often confounding for a former print journalist like me, who ended up in TV news because she caught the Memphis blues.

Marty glanced at the blinking light on his desk phone and chose to let it roll to voicemail. I picked up where I left off. “It’s going to take a little bit longer for my voice to come back.” I was working my way towards the big ask.

Marty looked at me, expressionless, waiting for me to provide more than just problems. I focused on his dark brown eyebrows and kept going. “These daily stories I’m doing are getting in the way.” Marty stayed in listening mode.

I pivoted to my solution – stop the stories and spend the next week or so in the Dallas school district’s business and financial office researching further shenanigans on the part of Maxwell Construction in connection with the earmarked federal monies. It would give me enough information to put together four, maybe five stories that could air in rapid succession – day after day after day. I figured Marty would like the idea since it dovetailed well with his goal of legitimizing the nascent local television news scene with investigative work and in-depth reporting.

After listening to my plan, Marty said okay, with a quick follow-up reflecting the inherent push and pull of the immediacy of television news. “How long before you get your voice back?”

“It could be a week, maybe,” I said, fingers crossed. I walked out of Marty’s office as he picked up the telephone from its cradle. Even though I had closed the door behind me, I heard his resounding response to the person on the other end. Marty was pissed, his voice a quick bellow, which startled me. I turned back towards the glass wall of his office — the phone in his left hand, Marty stood behind his desk. In one fell swoop, he bent his tall body, pounded the desk with his open hand and bellowed, “Goddamn it.” His deep, loud roar hung in the air, followed by his full-throated voice. “What the hell is going on out there? Did you get the goddamn video?”

The noise from the news director’s office grabbed the attention of numerous colleagues, to no surprise. I saw Sparky attempting to get my attention, walked his direction and let him know I’d get in touch when I got to the school district to give him the status of my story about teacher pay raises. I then hustled out from under the cacophony of the newsroom and headed in the direction of employee parking. But first, I would pass the “wall of shame” – a clipboard that hung from a large steel beam in the middle of the newsroom, covered in brown carpeting to match the floor. It was there that Marty posted notes every day, an occasional attaboy but mostly mistakes and fuck-ups a reporter or photographer had made the day prior. Every morning when I walked into the newsroom, I cringed as I stopped at the clipboard, turned and looked at the day’s posting, my eyes scanning for my name. The cringing was common practice among reporters and photogs.

When I arrived at the Dallas school district’s accounting office, the director was happy to provide me with yet another stuffed folder of receipts and invoices that would prove to be incriminating evidence for the feds to further analyze.

One day, I was going through payroll invoices attached to a list of employees who were due a paycheck during a particular two-week pay period. The money came out of the funds the construction company received from the school district’s desegregation monies for this project. As I looked over the list, I began to see a pattern — the same few names scattered across half a dozen pages. For example: Jose Lopez, Hector Garcia, and Randy Williams showed up in probably four of the six handwritten lists from just one pay period. Hmmm? This pattern kept appearing across the documents. Sure enough, the company was padding the payroll – bigger’n Dallas, as we exclaim in Texas!

There were maybe three folks working in the accounting department, where they let me set up shop at a vacant table, very handy for the hundreds of files and folders I perused and examined. I would often ask for lots of different invoices and notes to be Xeroxed (the word for “copied” back in that day). No problem, I got what I wanted. The staff had no clue what was going on with payroll, having little time to evaluate the invoices that came into the office in a deluge. With the exception of gigantic mainframes requiring their own housing, computers were nowhere in sight during the 1970s.

“So, what are you looking for? What kind of story are you going to do?” One of the gals in the department was curious when I first set up camp.

“I’m not sure,” I responded. “Just checkin’ things out,” I elaborated.

My snooping around in the accounting department was somewhat novel at the time, since investigative TV reporters much like the fellow hired by Marty were known in large part for a look-see into the temperature of food laid out in buffets at popular Chinese restaurants and the cleanliness, or lack thereof, of kitchens found in various eateries around town. General assignment reporters, myself included, took on the task of feature stories to fill slots in the newscast – exotic pets, such as lion cubs and humongous snakes that slither around the living room; a man-watching club for women; a new barbeque recipe that caught the attention of a gourmet chef at a fancy downtown restaurant. Television news reporters were also gluttons for spot news – random four-alarm fires, car pileups that left multiple people dead, tornados that ravaged small towns.

Marty Hagg’s goal as news director was to set a new standard for television news as a reputable competitor with newspapers. His tenure at WFAA brought him many accolades for his crusading efforts to merge good journalism with television news, and one of the main elements was investigative reporting, which I reckoned would be the one thing that would give me a crack at bustin’ the glass ceiling. Simultaneously, I found myself wading through the fierce feuding and grinding competition that drove a workplace tainted with the patriarchy’s thirst to dominate women with toxic masculinity.

While Marty Haag’s newsroom was testosterone-driven via yelling, chair-throwing, fierce tension, and unrelenting competition, it was also plagued with behavior that would be seen later as the forerunner to the #MeToo movement. There was plenty of sexual harassment to go around and a good handful of sexual predators in the newsroom.

This unsettling environment could be found in TV newsrooms and other workplaces all over the country due to the sheer number of women who were entering the workforce during that time in history, thanks to Civil Rights legislation.

A host of men in all sorts of positions believed this tidal wave of women in the workplace was a generous favor from the patriarchy that gave them carte blanche to do what they wanted to the women who shared their work space. WFAA-TV was no stranger to that school of thought – hosting an array of men who exercised their perceived privilege to sexually harass women by bullying and treating them as less than.

Many women, myself included, blew off the harassment stuff as part of the job and worked our way around it by laughing it off or walking away. One experience of mine with sexual harassment was when a prominent news anchor walked up behind me at a staff meeting in the newsroom and popped my bra. I turned my head around; he smirked and laughed; I walked away.

My other experience with harassment – almost a daily occurrence – is actually comical, especially in retrospect. The story comes courtesy of the assignment editor, Bert Shipp, who nicknamed himself Hoss. For the most part, he held sway over the allocation of daily news stories we covered.

Every morning at Channel 8 News, reporters found their way to his desk to discover what story Hoss was offering them as they meandered into the discordance put out by the police scanners near his desk. “... (scratchy noise)... Roger that… (scratchy noise)... Subject now fleeing on foot… (crackly noise)... Confirm eastbound on Henderson… (scratchy noise)... Enroute to location… (crackly noise)...”

One particular morning, walking up to Bert’s desk, I paused to watch him taking a drag off a cigarette situated between his lips. (People could actually smoke at work back then.) The drag taken, he deftly removed what remained of the cigarette stub, flicked the ash into one of two ashtrays on his desk, and looked up at me with a big ol’ smile rimmed by a full-bodied salt and pepper mustache.

“Well, little filly,” he said with gusto, “I have some protesters at City Hall stirrin’ up things at noon today.” His smile frozen in place, he awaited my response. “Okay,” I said.

I learned to take the moniker “filly” – the word used to describe a female horse too young to be called a mare – with a grain of salt, as did many of the women reporters in the newsroom.

In addition to the sexual harassment guys, there were the sexual predators – motivated by control and an expectation of sex. Some women in the newsroom fell victim, an emotionally devastating place to be. The power-differential was prodigious – the need to be gainfully employed was immense and there was nowhere to turn for help.

The predators I heard about through the grapevine; and, like many colleagues in the newsroom, I made an assumption about why a young aspiring woman anchor might have committed suicide, given that she allegedly had been engaged in an affair with a high profile reporter/anchor who never made good on promises to leave his wife. Many decades later, I was privy to predator stories detailing sexual encounters between women reporters and various men in the newsroom.

Back in the 1970s, women did not talk to each other about sexual harassment, much less sexual encounters of various sorts. Many feared they would be shamed by their colleagues or lose their jobs if they divulged or complained to management.

I was lucky I never had to deal with the predator-type, except one time, late into my career at WFAA, when Marty Haag plied me with delicious white wine during a weekday lunch he invited me to. I picked up on his vibe, and after we finished eating and chatting some more, I politely excused myself, citing phone calls to make and work to do. Funny thing was, he knew I had come out as a lesbian. It was no secret in the newsroom that I had undergone a transformation from straight to not so straight. I figured he thought I might be a good get if I drank enough of that delectable white wine.

I also dodged much of the #MeToo atrocities in the newsroom, most likely because I was in many ways disconnected from men – I wasn't one to flirt and was prone to rebuff their flirtatiousness. When I was studying at SMU, a friend let me know my reputation on campus among the boys was that I wore a chastity belt. It seems I took that armour with me into the workplace with success.

Now, back to that hunt I was on to literally find my lost voice. It eventually returned just as I was wrapping up the string of school district stories laying out the fraud and deceit perpetrated by Dallas school district employees and a construction company. For a week, my bombshell stories ran on both the six and ten o’clock newscasts. Marty was pleased with the attention that had come to WFAA. During the investigation I received a death threat, the tires on a news unit were slashed, and one of the Dallas assistant superintendents threw a heavy tripod at me. He missed.

The TV station Marty reigned over was owned by the Belo Corporation, which also possessed one of the city’s two newspapers, the Dallas Morning News. I’m pretty sure the Morning News had no intention of seeing itself as a competitor with a TV station that was, to boot, its nextdoor neighbor. And print journalists at the time hated “to follow” a TV journalist’s breaking story.

This explains, in part, why the Dallas Morning News didn’t give my reporting much attention when my investigative work into the school district’s use of federal monies was beamed out on WFAA-TV airwaves. My series was met with skepticism by some of the newspaper’s reporters, on up the chain to the editors.

According to one of my sources, the powers that be in the offices upstairs at the Morning News questioned the accuracy of my reporting. It did not help that I was a woman doing investigative work – not ladylike at all and somewhat shocking!

At the time, men had the upper hand in the world of journalism and controlled the industry at every level – from editors, all the way down to the print journalists who did most of the reporting. TV news was a joke among newspaper men and the few women scattered among them – disparaged by both as “not real journalism.” Au contraire — my work turned out to be solid, accurate reporting that turned up numerous examples of misspent federal dollars, which led to federal indictments and jail time for some. The Dallas Morning News had been scooped! By me, a blonde…

After my multiple award-winning investigation, I moved on to Fort Worth and uncovered corruption in that district’s school bus maintenance department. After a couple of these stories aired, a supervisor in the department committed suicide, with blame assigned to me by school district officials. Truth be known, the day I interviewed this supervisor, I had no idea he was at the center of any financial shenanigans. In my interview, I asked him to explain the Fort Worth school district’s requirements for buying batteries and tires and whatnot for buses. All I can figure is that he was eaten up with guilt about his cheatin’ ways before he ever met me. Not only that, word was out after the suicide that his wife had been leaning on him to put a swimming pool in their backyard. Poor guy had to get the money somehow.

With the Fort Worth school bus investigation, I notched things up a bit by using a computer to help me analyze the information I found in receipts and invoices. Use of a computer for any type of television news during those days was unheard of. But the idea came to me while flipping through the mounds of invoices and receipts I’d gathered, trying to imagine the best way to analyze the Fort Worth school district’s finances.

In a true ah-ha moment, it occurred to me that a computer would solve the issue and take the strain off my brain. But here’s the rub – computers at that time were only available as mainframes, mammoth metal boxes sprawled across an expansive room lacking in windows and sparse in doors. But what the mainframe did that interested me was crunch numbers and process huge amounts of data quickly.

The only mainframe I knew of was on the campus of my alma mater, Southern Methodist University, so I called over to the office that housed it, got the boss on the line, and introduced myself, not only as a reporter but also as an alum. I told the fellow what I was trying to do and asked if I could use the mainframe to look for a pattern in the expenditures. He easily agreed, much to my delight.

A few days later, photographer in tow, I carried sheets of paper filled with numbers into the building on SMU’s campus where the behemoth was housed. The fellow I was working with translated the information I’d collected on tires and batteries in particular and fed it to the mainframe, which spit out the answers to my questions, proving that a couple of supervisors in the school maintenance department were in cahoots with several local tire and battery businesses. The office of the superintendent tried to put everything back on me by post-dating a memo with content that contradicted some of my findings.

The memo, which the superintendent claimed was in a file I had gone through, was typed on a fresh sheet of paper that stood out from all the other memos in the file, which showed wear and tear. I wrote a story about that incident, in which the superintendent more or less admitted the memo was a plant to make me look bad.

No doubt about the anxiety I endured – the supervisor’s suicide, efforts to discredit me, pressure from the news director to keep uncovering dirt, revealing cheating and stealing among big city departments. I was exhausted. One day, when I was shuffling through boxes and files in a room set aside for us in the school district’s main office, a woman I did not know or recognize walked through the open doorway.

“Are you Kay Vinson?” she asked. I looked up from the box I was scrutinizing. “Yes, I am,” I said without a hint of trepidation.

“So, you are the one who killed my husband,” she said, disdain wrapped in her voice. “I just wanted to come by and see what you looked like in person.” She stared at me, a glare in her eyes – apparently, she wanted to see in the flesh the reporter who caught her husband stealing from the school district. The dead man’s wife would not let go, her mean-spiritedness on a roll. I wondered who in the hell told her where I was and then let her find me.

Those back-to-back investigations had taken the wind out of me. I walked into Marty’s office one day to tell him I wanted to move away from the intensity of investigative reporting, get into management, and learn other aspects of television news. He was sitting at his desk, and I sat down across from him. Bent on proving that TV news was much more than fires and car wrecks, that it was investigative work and “think” pieces, Marty looked at me and, in so many words, said no.

“I cannot take a winning racehorse off the track.” I was taken aback, got up from the chair, mumbled words I don’t exactly recall, maybe something like, “Okay, thanks.”

My response was to find another job. A colleague mentioned an opening in Austin at KVUE-TV that might fit the bill for my desire to learn management skills. I picked up the phone and called the executive producer at the station who knew me by reputation and hired me on the spot. I gave Marty notice I was quitting and then left for Austin, where I spent a year producing the six o’clock news and simultaneously realizing it was not the professional trajectory for me. I reached out to Marty, who offered me a job to come back and work in the Close Up unit, which gave me the opportunity to choose my topic, research, write and produce long-form pieces. Without hesitation I accepted, as it was a dream come true. Many of the stories from my final stint at WFAA focused on civil rights, human rights – access to abortion, women’s health issues such as premenstrual syndrome (saying the word menstruation on television was a no-no until I used it unabashedly) and then there was the much delayed lack of implementation of federal affirmative action programs at my alma mater, Southern Methodist University.

It was a tricky time for me since I was smack dab in the middle of that existential turning point in my life, claiming my full lesbian identity, and finally finding my lesbian voice, which happened in stages.

My first lesbian lover Sara and I parted ways after returning to Dallas from Austin. Soon after I found myself in the Close-Up unit I got together with a gal who also worked in television news as a photographer. Then I departed that relationship after more than three years.

And then, thanks to Sappho – whom I credit for guiding me along the tricky route to the Isle of Lesbos – I took up with a woman who was consequential in upsetting the fruit basket that was my early lesbian life. I interjected myself into lesbian politics with her, and we opened a lesbian/feminist bookstore in Dallas. Read all about it.

P.S. Initially, and then for decades after, I wrote off the literal loss of my voice as a “psychosomatic thing.” Turns out that might have been true. Now I know its proper name – psychogenic dysphonia, which comes to a body without giving a hint of its origin. I had some of the symptoms – not much of a voice, limited range and resonance.

Research shows psychogenic dysphonia occurs primarily in women between the ages of 30 and 50, prime years in the workforce. The condition is brought on by anxiety, distress, or depression. No surprises, just the tragic notion that women can lose their voice in a finger snap – under the weight of various stresses, whether family crisis or pressures from patriarchal rules and regulations.

The defining decade of adulthood (at least for us Baby Boomers) was our twenties, when big moments came rapidly – careers, marriage, children (or not). These are riveting, anxiety-driven, and intense moments in time. As we moved from our late twenties into our thirties, research suggests personalities usually change more than they ever will, and the brain has its last major spurt of growth.

The timing of my voice’s leavetaking was flawless and hewed to the research findings regarding psychogenic dysphonia. I tried to remain tough and hard-working during those times and managed to do some of my most incredible work. The departure of my voice probably gave me permission to ask for time to do the necessary investigative work in the Dallas school district’s accounting department. And that lead to a crack in the glass ceiling.

If you are finding my work valuable, meaningful, or inspiring, I’d truly appreciate your support with a paid subscription or one-time donation. In gratitude.

This is an excellent story of those prime years of your life! The losing of your voice, actually and symbolically, which led to your unique investigative reporting.. the busy newsroom… the coworkers… all colorful and vibrant. Brava!