Homage to Typewriter

The clicking, clacking sounds of a manual typewriter are marvelously musical, making magic that — poof! – puts thoughts to paper, arranges musings into sentences with the likes of commas, periods, and exclamations, then clusters the sentences into paragraphs that fill up single pieces of typing paper, whether lickety split or slow as molasses.

The maestro – the writer – makes magic, as with dancing fingertips upon the keyboard, whether two-steppin’ or free form. In order to lay down the words that make the story on page after page after page, the writer embraces the magic of the typewriter’s inherent creativity, much as a guitarist, fingering the strings in delicate and deliberate ways.

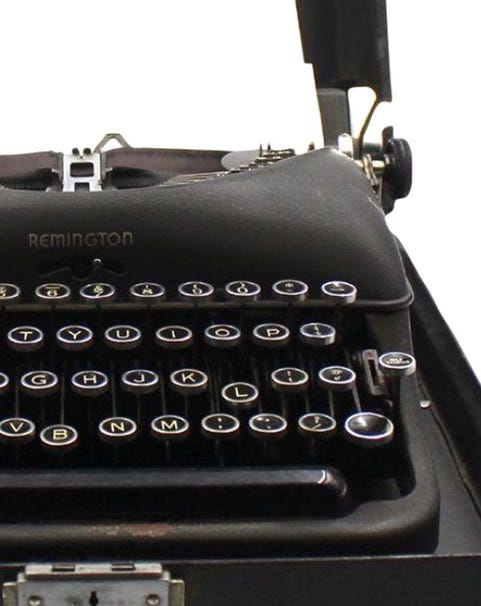

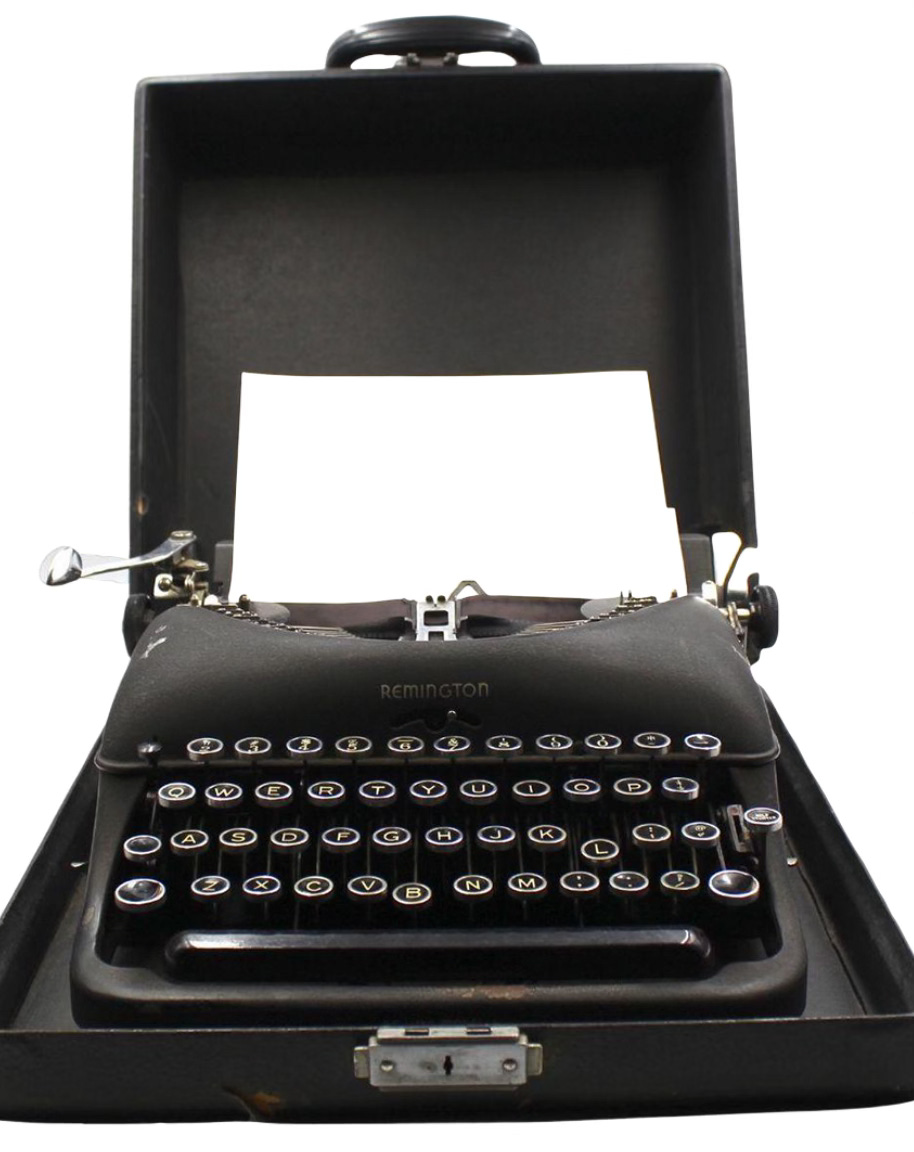

Without really dating much, my manual typewriter and I started going steady when I was in seventh grade. My mother gifted me a portable Remington typewriter she claimed my father’s father had used as a foreign correspondent in Mexico City – filing stories for The Dallas Morning News, Collier’s magazine, and other publications. He also wrote a novel — Jangling Bells — that earned him a stack of upbeat rejection letters, which he kept until the day he died.

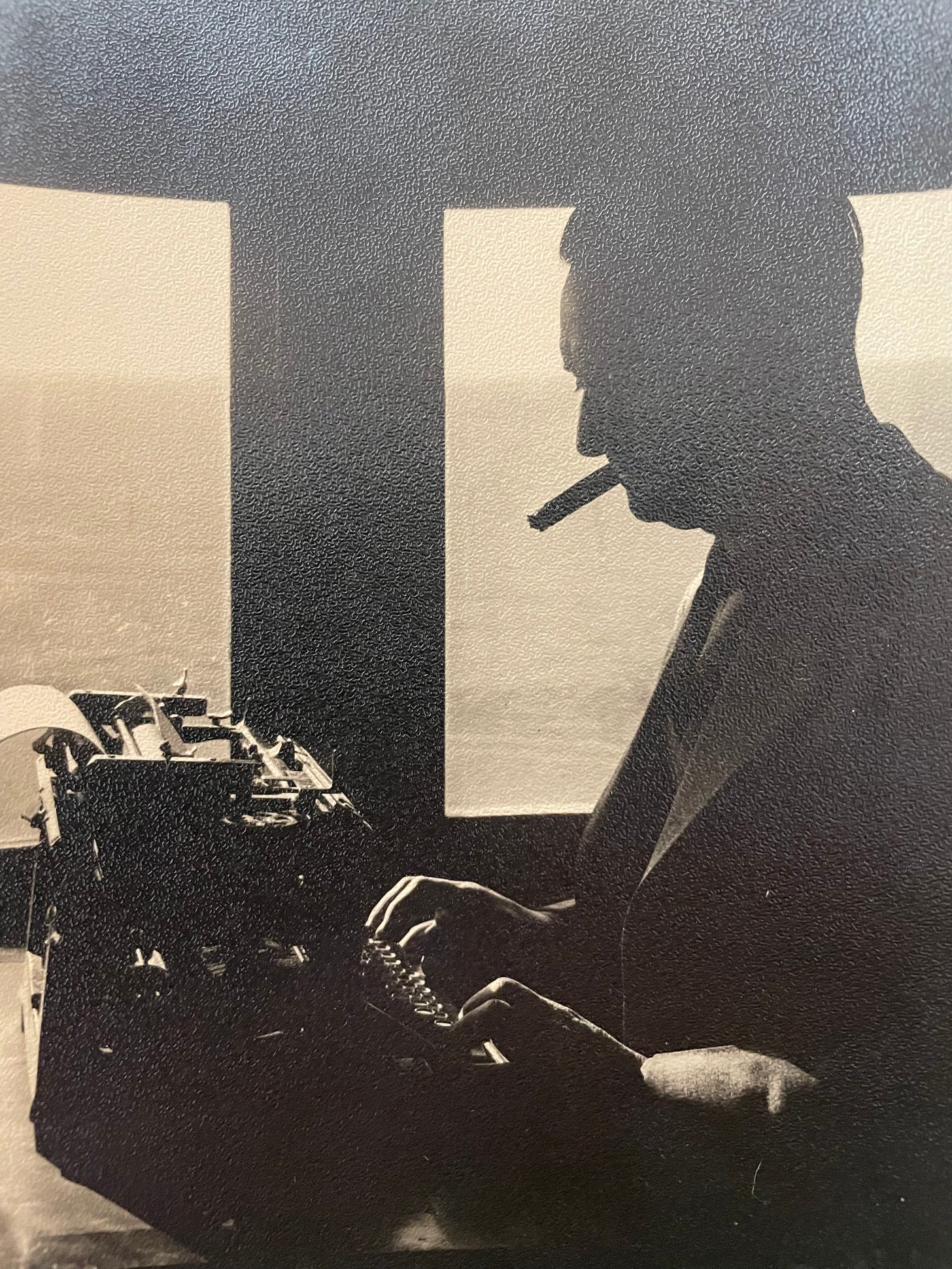

My mother’s description of my grandfather’s career as a journalist who traveled the world captivated me. That my grandfather’s typewriter was mine took my breath away. While an intoxicating surprise at the time, I learned many decades later it was nothing more than a fabrication when I came across a photo of my grandfather typing away. While the graininess washes out the background, I’d like to imagine the photo was taken as he crossed the pond between Great Britain and the U.S. on one of his many travels abroad.

The typewriter my mother gave to me and claimed was my journalist grandfather’s looked nothing like the cumbersome one in the snapshot above. To further confirm which machine belonged to whom, I came upon a repair receipt of my father’s for a typewriter that fit the profile of the one I had. It came as no surprise to me that my mother had most likely made her claim about the typewriter to fit her narrative that my daddy did not exist.

After her divorce from my father, Curtis, my mother, Mozelle, was dedicated, it seems, to keeping him away from his two young daughters, most intently after he landed in a federal penitentiary because he wrote a string of bad checks and then crossed a state line – a mortifying situation for Mozelle.

She could not bear the stain she suspected it put on her reputation, so she tore up the letters he sent her from prison, not telling her young daughters one iota of their daddy’s whereabouts or even relaying any thought of his existence, much less the contents of the letters, which were always filled with questions about “the girls” and how we were doing.

Mozelle fessed up about the letter-shredding way into my adulthood, though I can’t remember a time when she apologized or expressed regret over her behavior or how it might have traumatized me and my sister. Overall, It’s a sad story.

I’ll return to it later, but first let’s get back to my first love, my seventh grade steady, a portable manual typewriter, similar to this mid-century Remington.

My love affair commenced in 1963. The first semester of seventh grade had barely begun, and while I wasn’t sure if I liked Latin or chorus class, I knew I was head over heels with typing class. As luck would have it, I had my typewriter at home to practice on. I knew without a doubt this typing thing was for me, and not because I yearned to be a secretary in my adult life — no, siree! Not my style. Papa Vinson had set the bar. I wanted to be a writer and foreign correspondent — as international journalists were called then — just like him.

My typing class, taught by Mr. Smith at South Junior High in Salina, Kansas, trained my fingers to find the correct letters needed to form the words and sentences I was reading and copying from a piece of paper on the desk to my left as Mr. Smith kept his eyes on the second hand of his wrist watch, counting down one minute. At my best, I could type 70 words a minute with two mistakes. Great skill for a secretary, but not necessary for a writer, I would later learn.

The days in class when we wrote sentences and paragraphs, my fingertips learned to dance on the keyboard, my eyes on the words and letters interlaced on the paper, the art of peck-peck-pecking in search of the appropriate letters of the alphabet. The bottom line was to turn the peck-peck into a smooth move from one letter of the alphabet to another until the word was spelled out and sentences came to be, soon morphing into paragraphs. The End.

After gifting me the typewriter, my mother elaborated on snatches of stories she’d told me about my grandfather and his work as a foreign correspondent in Mexico City. She told me Papa Vinson, as she called him, had taken his family with him – my father, Curtis, who was maybe 5, and his mother, my grandmother, who was British. Her name was Clarice. She and my grandfather took up with each other during World War I, when he was stationed at a Navy base at the southern tip of Great Britain.

When my mother turned over my grandfather’s portable typewriter to me, I never made the connection that she was attempting to apply salve to the bruise-inflicted drama she dragged me and my sister into – the acquisition of a stepfather, a man she had known barely two months before they tied the knot. I suspect she thought she was doing all of us a big favor by getting a man in the house. Mozelle went without one for several years after she and my father divorced. At the time, divorcees, as they were called, were not held in good standing – marriage being the imperative for women of that time.

The nuptials led us to Kansas, a state I did not know. It was 1,000 miles from the home I had known in the boot tip of South Texas. When we first arrived in Salina, my young self – two summer months away from fifth grade – was speechless, having never seen an endless field of wheat or sorghum, nor felt my hair whipped around by prairie winds, nor heard the word tornado. I was completely out of my comfort zone in so many ways, especially with the stepfather thing.

My mother desperately focused on this new family of hers as it took form, rarely bringing up our past life in Texas. She did not want me or my sister attached to our daddy in any way. Maybe Mozelle was hoping we might instantly see the stepdad as an asset — or at least “better than” what we’d had. But things eventually went south in oh so many ways. For me, he was an intrusion of great magnitude.

I’m not sure my mother ever told the prison story to our stepfather. Otherwise, I’m sure he would have brought it up to us as a taunt. He often told me I talked too much. He chided me about a short story I wrote. He clearly did not like women.

My mother began to turn more and more to booze while turning the discipline arena over to him. He shouted insults, slapped us with a belt, hit us with his big man hands. This was violence we had not known — on ourselves, on our mother. I had a countdown going in my head and always knew just how many more years, then months, then days I had before I was outta there. I learned early on that I had to figure out ways to survive this messiness and trauma.

The typewriter became one of the coping mechanisms. A glance into the rear view mirror uncloaks the notion that Mozelle knew what she was doing by giving me the typewriter — no matter whose fingers had used the keys before mine. She was intuitive that way and knew I would learn from her gesture.

I kept the typewriter on top of the small desk in my bedroom, and I was in awe of it. The best gift ever, always present, always in my line of sight. When I sat at my desk on the second floor of our split-level house, I could look out the window at puffy clouds floating in a baby blue sky above the expansive wheat fields. Life in America’s bread basket, while boring, did provide a vastness to its skies that was awe inspiring.

When I moved into my junior year of high school, I took up smoking cigarettes, lighting a few here and there from my mother’s stash. I started smoking because I thought it enhanced the writing. This, after watching TV cop shows that depicted newspaper reporters smoking like there was no tomorrow, especially when they were pounding away on typewriter keyboards, eager to get the story put to bed.

A half-gone cigarette hanging off their lips, lots of smoke curling up around their faces, the TV pictured men razor-focused on their typing. (It was always men who were the reporters, but that never dissuaded me from wanting to be one.) Then, when the guy needed to think about what to write next, he would take a drag off the cigarette — no fingers involved — and more smoke would meander through the scene of intense peck-peck-pecking.

I practiced this skill of taking a drag off the cig as it hung from my lips while typing intently. I noticed that in order to fully accomplish the maneuver, I had to not cough and keep typing. I never learned this skill. Too much smoke in my eyes.

My top favorite writer at this time was Ernest Hemingway, who smoked and drank liquor with abandon. An American novelist and journalist awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953, and the Nobel Prize in Literature a year later, Hemingway’s writing technique is elucidated with words like minimalistic, understated, economical.

I mostly read his novels – For Whom the Bell Tolls, The Old Man and The Sea, The Sun Also Rises – and mixed in a few of his short stories and poems. I emulated his style in the short stories I wrote. My plans were to some day write a book, as I referred to it, not a novel, and certainly not a memoir, as I was not ready to have that notion cross my mind. So, this was the time in my young life when I began to equate writing with journalism, and the smoking of cigarettes and drinking of booze.

The typewriter was my key to sanity while behind bars in Salina, Kansas, out in the middle of nowhere, as I walked through my teenage years with a frustrated gay man for a stepfather and an alcoholic mother who would later confide in me that, had there been a gun in the house, she would have shot the son-of-a-bitch — my description, not hers.

Here are a couple of lines from a short story I played with during those high school years.

How can I live in Kansas and expect anything to change? Daily, I sit here at my window watching. Looking out over the endless plain. I pull a cigarette from its pack. Strike a match. Smoke seeks the draw of a breeze from the open window…..

You know, this is the first time I've connected my urge, as a ten year old, to write, with saving my autistic self from the world. Thankyou.