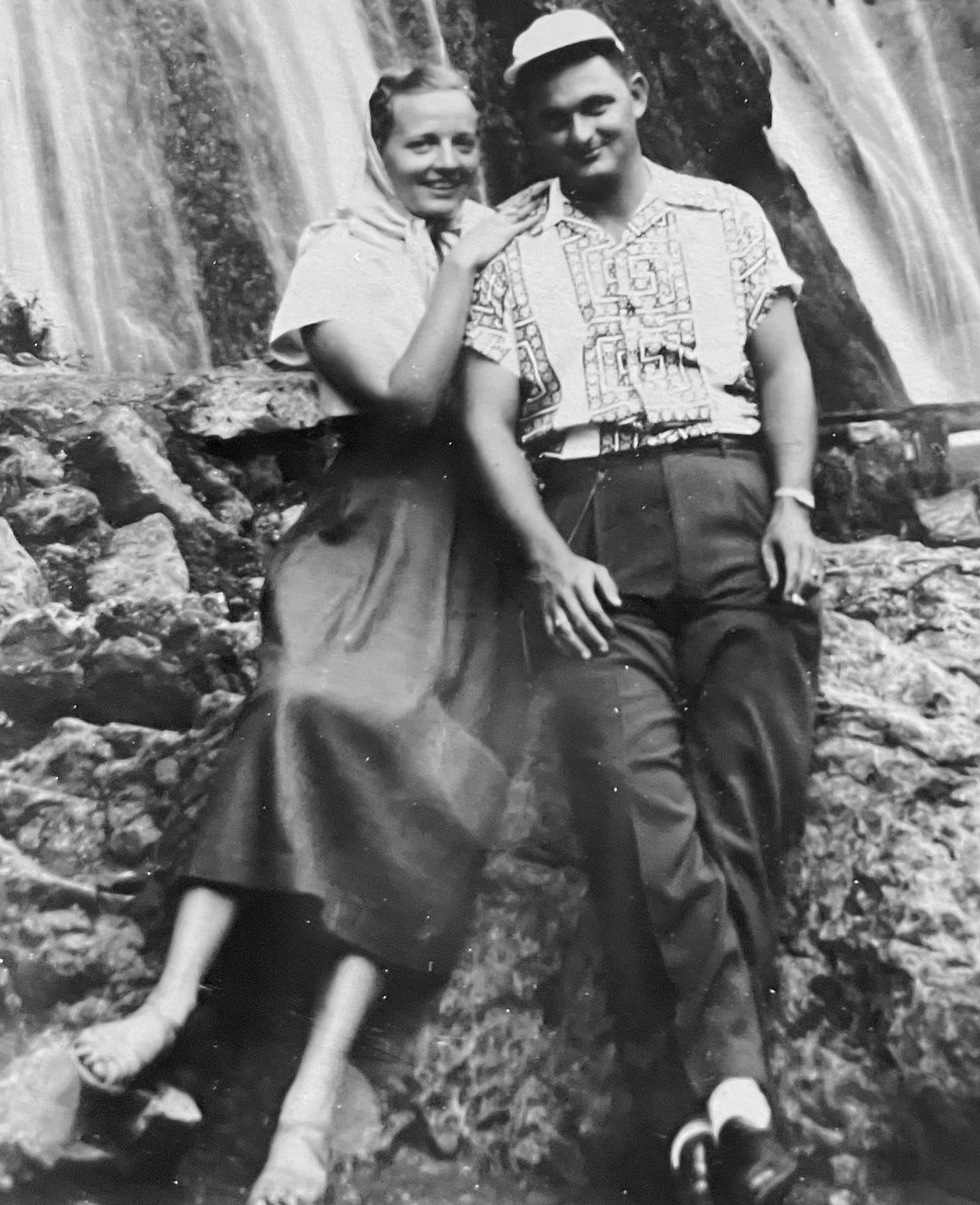

Mozelle and Curtis, my mother and father, at Horsetail Falls near Monterrey, Mexico, in late August, 1950. It’s their honeymoon, but the marriage will not endure.

THE OPENING JINGLE, a cheery toe-tappin’ tune, signaled us kids to get in front of the living room TV – fast. Time for Leave it to Beaver, a weekly series focused on the mishaps of a young white boy – nicknamed Beaver – navigating life in one of the many white suburban neighborhoods popping up around big cities. He was cute, precocious, freckled and sported a dimpled smile. Oh, boy! So all-American.

The first season of Beaver’s tales hit the TV scene in 1957, one of many series premiering on television that set the tone for patriarchal gender roles, firmly relying on propaganda to implant false narratives and definitions of males vs females into the culture.

It was the post-World War II period of the Fabulous Fifties, which saw a proliferation of technology for American homes, including television, which reinforced the great modern-day, patriarchy-inspired grooming experiment that had wives at home cleaning, cooking, and taking care of children while husbands left the house everyday to go to work, never cooking unless an outdoor grill was involved.

A beautiful dream, our leaders promised us, would blossom from this decade. For some, perhaps. But for many of this generation, it didn’t turn out so great.

My mother and father were among those who had a difficult and unpleasant time with the dream. Because the dream was a fantasy. It was tedious and demanding. Sometimes it could turn into a nightmare for those who chased it.

Around the time of the Beaver’s debut, my mother had already become a single mother, anathema in the culture of those days. She was a public school teacher, one of the few jobs given the seal of patriarchal approval for women. Other “acceptable” jobs included nurse, stewardess and secretary.

While Mozelle’s elementary school teaching job got a thumbs-up from the boys, she could not avoid the dreaded divorce curse they laid on her and other women — Scarlet Letter of the Fifties, the D. These women were given a title: divorcee. Mozelle had a pretty deep reservoir of perseverance – so, chin up and head held high, she moved on after divorcing my father.

My father, who had grown up as a pampered only child, and in spite of his handsome, dapper, well-mannered ways, did not have what it took to hold down a job. And he liked the booze. The day he left our family, I was having my tonsils taken out. It’s possible my sister was not having her’s removed, and was just there tagging along. I was six and she was not quite four. The year was 1957, more or less.

When we returned home, our mother pointed out there was a note from our daddy on the laminate kitchen countertop — beige punctuated with a soft white, galaxy-looking pattern. The counter was edged with polished aluminum strips. My glance couldn’t help but land on countertop speckles, as I watched in slo-mo as my mother picked up the note and took it in silently.

“What does it say?” I tried to read my mother’s face, a blank page.

“Your daddy left,” Mozelle said matter-of-factly.

“When is he coming back?” I asked.

“I don’t know. It doesn’t say.” These were the only additional facts she was willing to divulge.

My younger sister said nothing.

I stared out the window of the sliding glass door into the backyard, wondering what all this might mean. But I didn’t ask any more questions because the distinct message from my mother was that now was not the time.

It was early summer, maybe late spring. The backyard was green and lush with banana trees, hibiscus bushes and fence-to-fence carpeting, thick blades of grass. I longed to step my bare feet out there, walking them through the lusciousness of the carpet grass, my destination the swing set.

“Can I go outside and play?” I asked my mother. I kept my eyes focused on the greenness, waiting for an answer.

One hand on each side, I held tight to the large glass jar with a screwed-on metal top. Inside were my freshly removed tonsils, two tiny jelly-fish floating in a gulf of formaldehyde. After the extraction procedure, the doctor asked if I wanted to take them home. My guess is he asked that question in response to a question I asked him about my tonsils. What did they look like? How big? Something like that.

My mother bent down, looked at me with a smile, then touched my shoulder. “Kay, you’re standing here holding that jar of your tonsils. What do you plan to do with them?”

I shrugged.

“Yes, you may go outside,” she said, making sure to correct my grammar from “can” to “may.”

“I’m going to put them on my dresser and then go outside.”

I was sad that my daddy was gone. I hoped he would come back. Wishful thinking.

We did have one last visit with him, though, shortly after the tonsillectomy, before he finally really disappeared. He had a job for a short time at the TV station serving the Rio Grande Valley at Texas’ southern tip, where he ran a studio camera.

One summery day, my mother drove us to Harlingen, just up the valley from Brownsville, where she pulled into a drive-in burger joint and ordered one hamburger and an order of fries for me and my sister. I’m not sure if Mother imposed that sharing thing because she was a penny pincher or it was her attempt to manage our body size. Probably both.

Our daddy walked up to the car and got in the passenger side of the front seat with our mother, then turned around, facing the backseat, where my sister and I were sitting. Neither one of us said anything, both of us had our eyes on him.

He had a soft smile. “Hi, girls.”

I said hi back. My sister, the same. I asked him several questions pertaining to his job. I was happy to see him but didn’t want to show it much at all. I hid that feeling so as not to upset my mother. After the day that his note appeared on the kitchen countertop, Mozelle did not speak of him. Her silence was cacophonous. Her messaging to me, clear – this daddy of mine, who I knew as very kind and sweet, was no longer part of our family.

I don’t remember ever telling my mother I missed him, but deep down I was really glad to see him at the burger place. He answered all my questions about his job at the television station. (Interesting that I would later come to work at a TV station as well.)

“Well,” he said, “I stand behind a big camera on rollers that’s taking a picture of the person reading the news.” I had a visual of that as he described his responsibilities. He shifted gears and asked me and my sister how we were doing. We nodded our heads and said, “Good.” Then it was time to leave the burger place. First stop before heading back to Brownsville was Curtis’ nearby apartment. After driving by a string of palm trees lining a neighborhood street, my mother turned into a small parking lot.

Once inside the apartment, my daddy sat on the sofa, and my mother led my sister and me to the bathroom. She filled the bathtub almost full and gave instructions to my sister and me in a soft but firm tone. “Take off your shorts and shirt. Leave on the panties and get in the tub.” Her smile half-hearted, her lipstick an apple red, worn down to pale from the day’s doings.

Our mother then found some aluminum TV dinner trays in a kitchen cabinet for us to splash around with. Now that we were distracted, she sat down on the sofa with our father and they talked. This was the exclamation mark to his disappearing act.

“Okay, girls, time to go home.” Mozelle stepped into the bathroom with a couple of towels. We dried and dressed in silence, our father sitting on the couch leaning forward, his hands on his knees and his head down. “Bye-bye. Bye.” I looked at my father. He looked up and smiled.

I don’t remember if he got up and hugged me. I am holding out hope, though, that he did and that his deep blue eyes glinted with tears. Mine did.

Our mother continued to move us along, away from the event of our father’s leave-taking and, as the head of the household, she decided to focus on her single life with two small daughters. She rarely, if ever, spoke of her ex-husband and our daddy in our presence. My guess is that she wanted us to go along with her plan to forget him – as if it would be that easy.

In retrospect, I think it’s entirely likely she orchestrated the note on the kitchen counter, giving our daddy verbal instructions that he was to leave town at the same time I was undergoing a tonsillectomy, and then making the note appear. She never showed us its contents. Maybe the paper was blank.

That day I carried my tonsils home in a jar was the beginning of the tale of our daddy’s disappearance from our nuclear family. It was also the day I began to morph into Little Man, quickly learning the role my mother expected me to play in my father’s absence, one that involved responsibilities often assigned to the man of the house, particularly at that time in nuclear family history. And since we didn’t have such a man anymore, I got the job.

In the beginning, my mother would call me into her bedroom as we all got ready for bed in the evening and give instructions. She would tell me to make sure the doors were locked, the windows shut or sometimes left open. When the evening brought us balmy weather Mozelle liked fresh air finding its way into our house.

Her directives made me feel needed. Soon I wouldn’t have to be asked — it became part of my daily routine. Becoming Little Man created a kind of vigilance within, and also a sense of responsibility that grew to be an Achilles heel that’s never quite healed. Do they ever?

Little Man is not a nickname that my mother ever called me. In fact the label didn’t come to be until my mother’s passing in early 2015. During the months prior to Mozelle’s departure from life, my partner at the time was witness – bless her heart – to my telling of the many childhood stories clamoring for attention, anecdotes melting into a mural of my childhood, as my mother is waiting in hospice care for her time to go.

As the last few words of one of these random childhood tales rolled nimbly off my tongue, my partner interrupted me, as she was wont to do, and summed up the situation with her best Texas twang exclamation. “Yew were Little Man! Yep, yew were Little Man, doin’ all them things for yer mama.” She smiled big, her teeth bright as the night’s stars that light up the Texas sky.

At that time, the Little Man moniker took on meaning, felt like a good fit, a way to describe my role in childhood. So I stuck with it, used it in stories I’ve told around a campfire ringed with friends and also chronicled, like this one unfolding now. ….. to be continued

Here’s the kicker, a snapshot shortly following the d-i-v-o-r-c-e.

There I am on the left practicing various ways of modeling Little Man.

That day of the snapshot I was in El Paso, Texas, making a new friend, but only for a few days. His name having been lost to history, I only know him as the eldest son of a woman my mother befriended during her days at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. I recon this road trip my sister and I took was Mozelle taking a break from Brownsville and her recent divorce. She took in a bullfight one night across the border in Mexico with her friend and left us kids with a sitter. I remember nothing but fun on this visit.

I also recall this young baby boomer boy in the pic as sweet and kind, like his smile suggests. He shared his black cowboy hat and let me sport his gun and holster for the snapshot. It was a real treat since I was not allowed to have a gun in my limited toy collection. Besides, what’s a holster good for without one? — “tool belt” my lesbian self is typing.

I read this again, with more focus, and it brought tears to my eyes. Divorce is never easy on kids but parents can make it easier. I'm not sure I ever did a good job, myself. But this story deserves wide distribution. And your writing is excellent. I love this: "my telling of the many childhood stories clamoring for attention, anecdotes melting into a mural of my childhood," Well done, Kay!

Kay, This is very well written. I don't think I'd ever heard this story. Especially about your father and his leaving. I had a set of pistols just like yours.. And I think a Davey crockett hat

I remember getting my tonsils up too. We got ice cream..