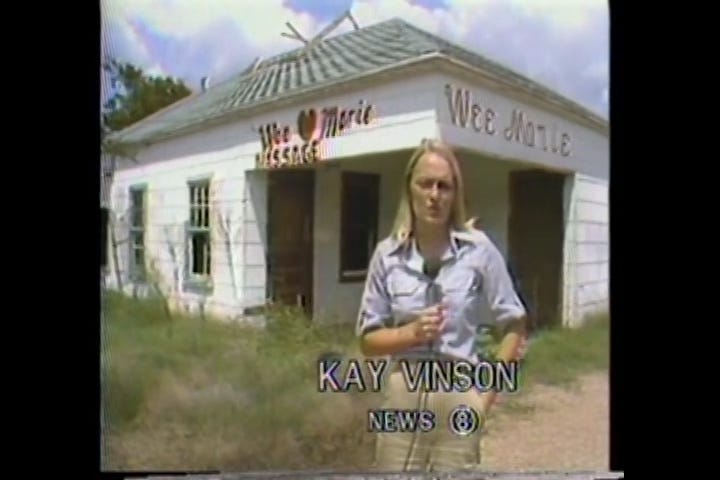

This particular day, the assignment editor sent me lickity-split to Wee Marie Massage – situated in a ratty rural corner of the county – to cover a raid by the Dallas County Sheriff’s Department following allegations of illegal activity going on under the covers. These types of raids were routine events to showcase Dallas County’s public crusade against immorality.

I hustled outside to the parking lot behind the TV station with my photographer-of-the-day to a light blue four-door Ford Galaxy, with its hefty motor and huge trunk. The news department had a small fleet of these cars, each one assigned to a photog, as we called them, and each trunk filled with the necessary gear. Driver and front passenger doors were emblazoned with the WFAA-TV/News 8 logo. The crackling two-way radio in the car kept us in touch with the assignments editor and the constant chatter kept us apprised of the rest of the news that was being chased that day.

By the time we reached the scene, Wee Marie Massage had already been shut down and only two sheriff’s deputies remained. The photog grabbed his camera from the back seat and I scoured the scene looking for the victims of the raid, easily locating one of the gals who worked there. In an on-camera interview, she claimed the raid was a set up and denied any illegalities. It was almost always the gals who were having to take the hit – time in jail, fines, loss of income, you name it – the guys paying for “massage” services got off scott free since they were so very rarely caught in the act – part of the rules of the patriarchy, protect your own.

This story was one of many I covered in the early days of my television news reporting. Most likely it was 1975. At the time, I was a general assignment reporter, which meant I covered all sorts of stories, “spot news” we called it – police raids, shootings, robberies, fires, deadly car wrecks. Every single day was a surprise – thrilling to those reporters who loved nothing better than careening in the news unit in hopes of having bragging rights to being first on the scene.

“Spot news” was not, however, my idea of news. In the case of stories like the raid on Wee Marie’s Massage, I was nothing more than a messenger for the patriarchal policies of local government. My goal was to be a reporter who dealt in content – pushing back against patriarchal policy makers and power brokers by delivering news to the public that was impactful, whether tax rates or paltry funds allocated for programs in public schools.

During those general assignment days, I looked to a colleague in the newsroom for mentoring. Our news director had hired a woman reporter shortly after I came on board who had a few years more experience than me in TV news. She was loaded with chutzpah, a real pistol, as some of us Texans might say. We’ll call her Carmen. She caught my attention straight away. Her first day on the job she noisily plunked down a gargantuan brown leather purse on the topside of a slightly battered and bruised metal desk adjacent to mine, turned to me and introduced herself. In doing so, she sort of threw herself around in big waves of movement. I wrote that off to her Texas heritage. Gals brought up in the Lone Star state often present as brassy and bold.

I was struck by her stunning Hollywood-esque beauty and intensity and knew immediately that she took shit from nobody. Most recently she had been a reporter and anchor at a TV station in San Francisco. Management there wanted her to lighten her hair so she would not appear too Mexican.

She told me that story not long after she and I became desk mates. “Really?” It was the only question that came up for me except, “You’re kidding?”

“No, I’m not kidding. Those guys were assholes. But I went along and let them lighten me up.” She tilted her head up to one side and smiled, revealing her whitened teeth. “Whatever it takes for me to get to network and anchor the nightly news on CBS!” She laughed. Loud, with a cackle to go with. Her lips were full, punctuated with lipstick of a rich red hue, and a coy smile. In short order, it was clear Carmen knew how to make herself look real good for TV. “The camera likes her” is how those of us in the TV news biz described it. She was also whip smart, which I later observed she used deftly to make elected officials squirm in their seats, those patriarchal naysayers who thought women did not belong in television news.

It wasn’t long after she was hired that our news director assigned her to cover Dallas County government. It was her “beat”, which meant she covered the goings-on of the Commissioner’s Court and the County Courthouse. Beats were the domain those days of newspaper reporters, but our news director had been hired to do things differently with TV news coverage and shifted the paradigm.

Off and on, when we had time in the newsroom at the end of the day or even in the midst of the usual chaos in the newsroom we would discuss potential stories and what sort of video would work well to help tell the story. Carmen encouraged me to learn how to use make-up and lipstick and to put more stand-ups in my stories, a good example is that freeze frame of me in front of Wee Marie Massage.

“You must put yourself at the scene,” Carmen insisted routinely.

“I get it, but I’m not comfortable putting myself on TV,” I said. “The story is not about me.”

“Well, get over it. That’s the way TV news works,” she shot back in a righteous manner, which I learned she was wholly devoted to. “Stand ups show the reporter on the scene,” she pointed out before raising her voice. “And furthermore, it is absolutely critical for viewers to actually see a woman reporting the news. We must make ourselves visible.” Carmen tossed her head of hair and grabbed a pack of Marlboro Lights sitting on her desk. She put a cigarette between her very red ruby lips, flicked a lighter, and took a long drag. Her exclamation point.

I wanted to know everything about Carmen and was beyond excited that our desks were next to each other. My instincts said Carmen was the mentor I needed. It was clear I could learn from her to tap into the aggressive and persistent tendencies I carried with me. I already had the smarts. What I did not intend to borrow from her, though, was coyness, red lipstick, and a sexy flirtatious manner.

Eventually, I did get with the make-up part of it, very critical for women. The camera loved us even more for it. That’s what Carmen preached to the five or six women reporters in the newsroom.

I took in Carmen’s work with a critical eye – especially the manner in which she acquired interviews and expected accountability from elected officials.

“Excuse me, Judge Sterrett. I have a question for you. It’s about the funds you authorized for that road project in south Dallas County.”

“Not now,” the crotchety county judge would say, his head down, his walk quick. It happened regularly, he’d turned on a dime, his back to Carmen as soon as she approached, microphone in hand, cameraman in tow. She would do a quick about-face and take off after him, inevitably catch up and corner the fella.

“The road project funds…Judge Sterrett. I have questions for you.” Carmen would focus a burning stare on him. “How do you explain awarding the road work project contract to one of your buddies? It’s called cronyism, Judge.” A string of words came out of his mouth. “You are not answering my question,” she would say with firmness. “Shall I repeat it?”

When an elected official shut a door to keep her out of a public meeting, she confronted him on camera because the meeting was by law open to the public and therefore the news media. In a democracy, folks have the right to transparency of their government. Carmen made that clarion call on a regular basis.

She was bold, aggressive and alluring, a contradiction of what the politicians – most of them men – thought should be the case. Pure and simple, she was not acting like a lady. The men wielding the political power were used to jawing with male reporters who weren’t sexy or truculent.

The good ol’ boys who ran the Dallas County Commissioners Court and the Sheriff’s Department were flummoxed by Carmen and often threw boyhood-esque tantrums captured by television news cameras. It was a sight to behold, their egos bruised, because a woman questioned, for example, their decisions to misspend folks’ hard-earned tax money. I learned quickly that the greatest thing about television news was the camera – great for catching bad behavior of politicians and passing it along to constituents on the nightly local news.

I wanted to be a reporter just like Carmen. She gave me permission to push back on the patriarchy, challenging it in a way I had not seen before, much less attempted. Whatever feminist traits I had, she supercharged them.

A few of my male colleagues were not shy about razzing me for chasing politicians down the hall, barging into a room with the photographer, camera rolling and microphone in hand. They called me a “copycat”. What did they know? I was following the lead of my role model. It was my aggressiveness training for the serious reporting work ahead of me.

While I considered Carmen my professional mentor, I also recognize in retrospect that I had feelings for her – more than friendship feelings, a crush sort of thing, maybe. It was her demeanor, pure and simple – a really good lookin’ gal who was a bad ass reporter – so, so sexy.

She would be one of maybe half a dozen women I found myself crushed out on before my husband and I divorced. I kept those intimate undercurrents to myself for the most part. After landing in Lesbian Land, I stopped counting.

Carmen had been reporting on the doings of the Dallas County Commissioners Court and the Sheriff’s Department for maybe a year or so when she became pregnant via a lawyer she met up with at the courthouse. After confiding with me about her dilemma, Carmen let on that she was expecting to resign from her job. While federal civil rights law required a company to provide paid leave, there were no real avenues available for women to file complaints, allowing companies to skirt the law and send pregnant women packing, often with hollow words: Give me a call when you are ready to come back and maybe there will be a position open.

Carmen expected our news director would find a place for her when she was ready to return, but if not, she would seek out her dream as a national television network political reporter in Washington D.C., the grand stepping stone to what she coveted, a national news anchor job.

The day Carmen planned to let our news director, Marty Haag, know she was pregnant, she pulled me aside in the newsroom and I followed her back to our conjoined desks.

“When I come out of Marty’s office,” she said, “I want you to go in immediately and tell him you want the county beat.” She knew, like I did, that the smell of blood would have one or more of the male reporters knocking on the news director’s door in no time. So, I needed to get my foot in that door pronto.

I looked at Carmen as my stomach turned. “I’m not sure. I don’t think I am ready to do it.”

It was a big step to move from general assignments to a beat — especially one involving government officials and holding the powerful patriarchy accountable — that’s when the training wheels come off.

Carmen looked up at me. She had been freshening her lipstick before going into Marty’s office to give him the news. “You are ready for this,” she said with a sliver of a smile. “You can do it.” Those few simple words are often what women say to each other in times of stress, moments of fear, voids of self-esteem.

“I’m not sure, Carmen. It makes me nervous.” I was frozen.

“I’m going in now to Marty’s office. I want you to go in right after I come out. I’m going to tell him to give you the beat. That you can do it.” Her words forceful, she stood up from her chair, tilted her head to one side, and walked into the news director’s office. When she walked out, it was my turn to walk in.

I took a deep breath. Time now for me to get my boldness on. I got up and walked towards the office, a small, drab place with glass windows offering a view of reporters and photographers zigzagging through old metal desks to the tune of a cacophony – scratchy, non-stop hubbub from police scanners and the two-way radio that linked the assignment editor to the gatherers of the day’s news.

I stuck my head inside the news director’s office, which he was housed in before the newsroom was renovated. The door was half-way open. “Hey, Marty. Got a sec?”

“Sure.” He motioned for me to step in.

I did not sit down. “I know now that Carmen’s leaving and you need someone to cover the county beat. I want to do that. I’m ready for it.”

Marty was a driven man who believed that fierce tension in the newsroom drove reporters to compete, striving to beat each other to the punch with aggressiveness and investigative work, which meant better stories for the station and better standing in the market.

“I’ve been watching your work, Kay. You can have the county beat.” His voice was nasal and often marked with pauses, as if thinking. “Let’s see what you can do.” He was a “just the facts, ma’am” kind of guy.

“Okay. Thanks, Marty.” I turned around and walked back to my desk. While I was nervous about the big move, I also was thrilled to be rid of daily “spot news.” Time to get to the meaty stuff. It wasn’t long before I started stirring things up with the good ol’ boys on the Commissioner Court and in the Sheriff’s department.

That county beat was a stepping stone to what was next on my list, the education beat, what I really coveted. And it was just short of a year before the reporter covering that beat found herself pregnant. After hearing that news, I walked straight into the news director’s office and claimed the beat. He gave it to me.

What next? I literally lost my voice and then I found it. (That story’s just around the corner.)

In hindsight, I see clearly that Carmen’s role in my life offered me a model – to be aggressive, take risks, push the envelope, even if I didn’t feel fully ready. This wasn’t only in the arena of television news – whether investigative work or stories about menstruation and other women’s issues – she also laid the groundwork for me to bravely come out as a lesbian and eventually open a lesbian/feminist bookstore in Dallas, the buckle of the Bible belt.

If you are finding my work valuable, meaningful, or the least bit inspiring, I’d truly appreciate your support with a subscription or one-time donation. In gratitude.

Go to the archives for more of my stories.

Beautiful

Loved this remembrance of that treacherous era … and remembered with such joy how you covered my foray into Title IX activism at SMU. You made me feel so affirmed at a time when I felt so battered by the prevailing patriarchal winds. Not sure I’ve ever properly thanked you for that. ❤️