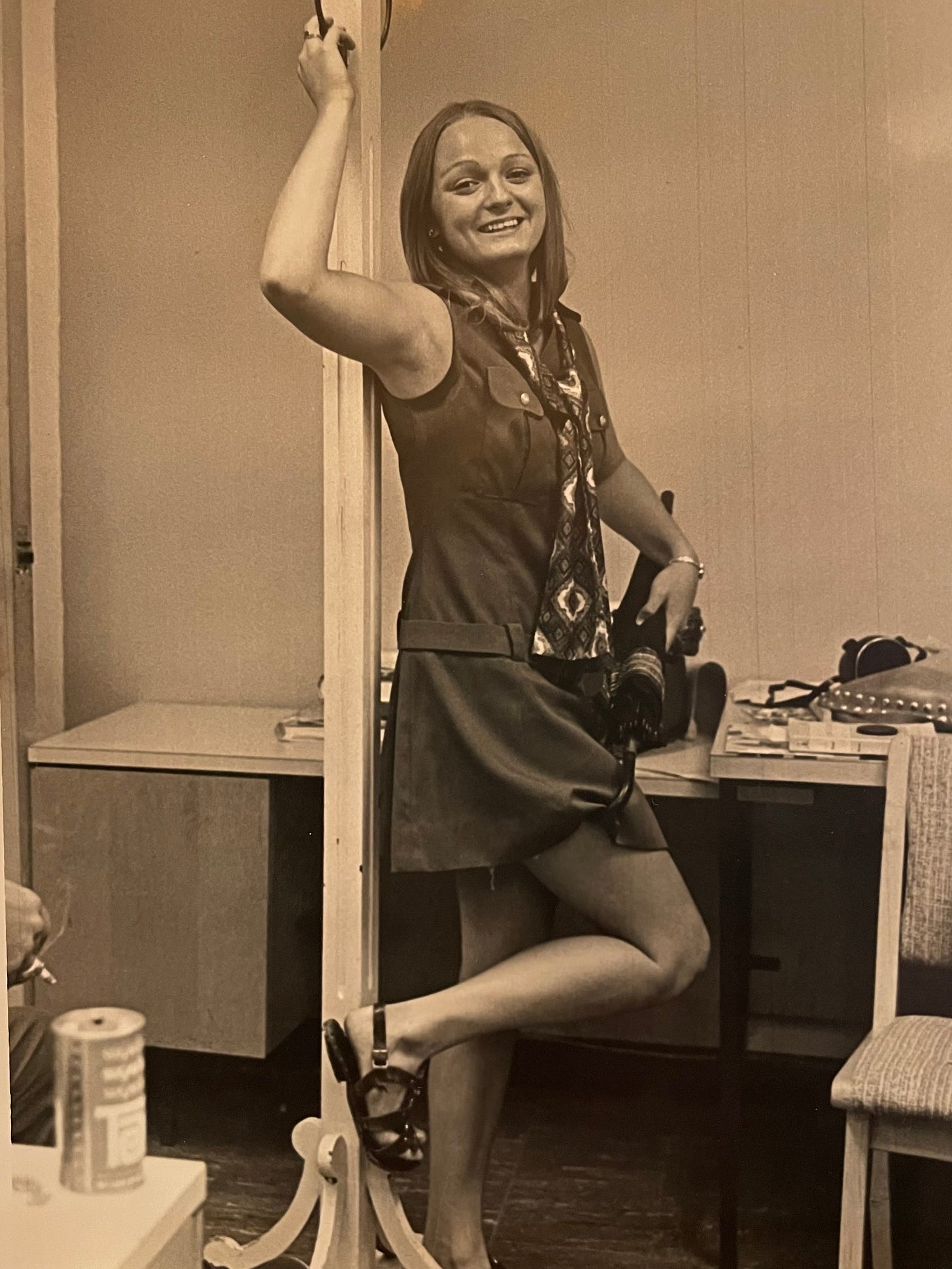

This snapshot – taken in 1972 when I was a year shy of graduating from Southern Methodist University in Dallas with a fine arts degree in journalism – is a pastiche of the traditional role of women. I was moved to have it captured following a rousing conversation in the office of the student newspaper, The Daily Campus, about the feminist movement – one of the civil rights tidal waves washing over the decade.

When I arrived at SMU as a freshman in unconscious lockstep with the patriarchy’s heterosexual requirements, skirts and dresses were required for female students. When I left four years later, pants were allowed. Renowned feminist Gloria Steinem had visited the campus and encouraged many of us young gals in the audience (myself included) to make good trouble and demand equal rights, like being able to wear pants on campus. Pants on women, of course, were frowned upon by the patriarchy, probably because there would be confusion about who wore the pants in the family. Additionally, pants make it more difficult for men to commit the crime of rape.

There hasn’t been one skirt or dress that I ever liked in my lifetime. My body did not cotton to the notion that girls and women were meant to wear them. They were uncomfortable and wholly impractical – climbing around on the monkey bars at recess revealed underwear, which got you a finger-wagging from the teacher; jumping rope and riding a bike could be awkward; and you always had to remember to make sure when you sat down in a chair to fold your skirt under your behind to make sure you were sitting on the skirt and your underwear was not touching the chair.

When I had a chance to wear pants it was heavenly, had me feeling grounded. Dresses were designed entirely to constrain our movements and show off our breasts, legs, and arms or to cover up the whole of our bodies – depending on the patriarch’s mood de jour. Besides, this whole mess of who is the appropriate human to wear skirts and dresses is the consequence of toxic masculinity, a scourge perpetuated by the everlovin’ frickin’ patriarchy.

Femininity in our American culture is defined as “womanly” stuff, circling back always to cleavage and breasts – which seem to fascinate and sexually arouse men, particularly when the breasts are Rubenesque, or simply busty. (My mother told me one time after a few cocktails that a rather curvaceous sorority sister of hers in college got stuck with the nickname “busty lusty”-- thanks to the boys.)

Breasts aren’t part of the primary external female sexual anatomy, but the vulva – made up of the labia, clitoris, opening of the vagina – is very much a part. Breasts seem to be a fetish of the patriarchy which interestingly, disappeared the clitoris, the key to the kingdom of a woman’s sexual ecstasy, the quintessence of femininity, what it means to be womanly. Go figure.

Back in those days of my young adult life, I didn’t really get what the patriarchy was all about, and wouldn’t put the pieces of the puzzle together until later. In my world, the word patriarchy wasn’t part of the vernacular at the time. We would just say the word “men” – in an exasperated way – and roll our eyes.

Now I understand clearly that it was the patriarchy that spread propaganda after the boys came home from World War II, during which time women replaced the male workforce. After the war and soldiers returned home, men took over again and women, for the most part, were sent back home. The soldier boys’ homecoming triggered a blitz of social constructs refined by the patriarchy during the 1950s that enveloped the country. In this case: men were to get a gal and marry, have babies, get a good job, put up a white picket fence, make perfect patriarchal families like the ones in “Leave it to Beaver” and “Father Knows Best,” make it so that little girls wore skirts and played with dolls, and put mothers/wives in the kitchen cooking, in the living room cleaning, in the baby’s room changing a dirty diaper. Women also transitioned from the pants they had worn at work to skirts and dresses, which were more revealing and much less practical.

Now, back to the days when I was still wearing a dress or skirt and blouse.

My first two years at SMU, I was getting traction in my classes and with my work at the student newspaper. A friend told me at the time the guys joked that I wore a chastity belt. I was not dating much — it wasn’t on my list of priorities. Same format I followed in my junior year of high school, when I occasionally dated a fellow who was very sweet, drove a two-tone (turquoise and white) 1957 Chevy Bel Air. I was his date to prom that junior year. I’m not sure we ever kissed, even at prom. Guess we felt comfortable and safe with each other. Looking back I’d lay money he was trending gay.

Senior year of high school, I dated a fellow named Fred who was a year older than me. He’s the one to whom I lost my virginity. “Ouch,” to say the least.

During one of my dates with Fred – maybe it was the time at the drive-in movie when we played “One is the Loneliest Number” by Three Dog Night at least half a dozen times in a row on the cassette player screwed to the underside of Fred’s Dodge Dart dashboard – he popped the question with a statement.

“I think we should do it,” he said, staring ahead at the movie screen showing a cartoon.

“I’m not sure.” I had suspected this topic would crop up again. Fred had mentioned it several times and each time I shunned interest – hadn’t ever seen a penis and didn’t like the thought of having one inside of me. Then I caved.

“Okay, here’s the deal,” I said. “If…we do it, it will not be in your car, parked in a dark field of sorghum. It’s going to be in a bed at your house when your parents are gone.” I could tell he was getting excited at the expectancy of the event. “Okay,” he said, not wanting to take the chance of me backpedaling.

Fast forward a few weeks, when Fred called me to let me know his parents were out of town over the weekend. When he picked me up that Saturday night, we went directly to his house and into his bedroom, where I continued reminding him that I was nervous.

“Don’t worry. It’ll be okay. Besides, you’re athletic and have probably already popped your cherry,” he said, bereft of any tenderness or concern.

“No, I haven’t popped my cherry,” I said, rebuffing his callous remark. However, as the patriarchal culture (my mother included) had taught us girls, most missteps were probably our fault, so I had second thoughts in my head – maybe I did pop that cherry in gym class while playing half-court basketball.

“Sure you have,” he countered and quickly unbuttoned his shirt, zipped down the fly of his pants, and took off his underwear while I did the same sort of strip down, only more slowly and with apprehension. We lay down on the bed – me on my back, him on me – and in no time he had stuck his penis in me and in fact, popped my cherry. That was it, a done deal. I got up immediately and went into the bathroom where I tidied up.

We did “it” a few more times – in the back seat of his car while parked in a sorghum field under the light of a silvery moon and lots of stars. I think one of those times I relented and sucked his dick. None of it was to my liking. I learned a dozen years later that with a lesbian girlfriend and a penis nowhere to be found “it” was a field of ecstasy.

My boyfriend Fred must have appreciated the backseat moments because he asked me to marry him after graduation from high school. At first I said, “Maybe. I’ll have to ask my mother.” I, too, it seems – like so many other girls and mothers – had soaked in the patriarchy’s propaganda about girls needing to marry ASAP and then have babies. But in the end, my answer to Fred’s question was no thanks. And I was off to Dallas, leaving Salina, Kansas, in the rear view mirror of my mean-ass stepfather Bill’s company car, a white Chevy station wagon. Good riddance to both of those guys.

It was at SMU where I met a fellow who caught my attention in a good way. Mase was his name and he was a journalism student as well. We both were reporters for the The Daily Campus newspaper, a prerequisite for the ladder climb to the editor-in-chief’s job, what we both wanted for our resumes.

As journalism comrades, Mase and I also became good friends. Our junior year was the time of Watergate – an unfolding scandal around a botched break-in at the Democratic National Committee offices in Washington, D.C., which led to the eventual take-down of President Richard Nixon for his efforts to cover up the crime. Nixon left office on his own, realizing impeachment was imminent. The core staff who worked tirelessly at The Daily Campus were bent on learning the ins and outs of what was involved in being a journalist, including following every bit of political news out of Washington.

Many of us juggled full class loads every semester with the work we were doing at the campus newspaper, learning the ins and outs of being protectors of freedoms – the press, speech, the First Amendment. We were driven to speak the truth to the public – to uncover the story, ferret out graft and corruption, challenge politicians to serve the public and not themselves. We were so very serious about it.

Our tight-knit group was very politically astute – attuned to the Vietnam war, Nixon’s drug war, the Civil Rights movement, the feminist movement, and there were hippies amongst us. The majority of SMU students rarely showed interest in occasional campus protests for civil rights or against a war, but they were enamored with the sorority and fraternity life. We wrote editorials in the paper chiding these undergrads for their apparent apathy, which we argued ran rampant and was disgraceful. If they responded, it was with whiny letters to the editor disparaging our liberal bent and giving us a hard time for not being supportive of the football program, which was awash in financial scandal.

My memory of Mase at this time is best captured in a black and white snapshot I’ve held onto all these years. He’s probably 20 at the time, wearing a blue jean jacket. His dark hair is wildly tamed, his tight curls soft and playful as he smiles with his eyes, his lips. A lock of hair across his forehead, underscoring the sweet look on his face. And all that coming together as one darn good-looking guy – a hippie filled with peace and love who wanted the Vietnam War to end. I was a hippie, as well, regularly flipping the peace sign in public but never wearing flowers in my hair, or adorning myself with long flowing skirts, the colors melding everywhere. It was okay for others, just not my style. That would be tie-dyed t-shirts made by artist friends and bell bottom jeans sold at the local Army-Navy store.

Mase and I both focused on our journey through SMU and our shared desire to be newspaper journalists. Our eyes were on the prize, we were working at The Daily Campus in various positions – reporter, columnist, associate editor and finally the prize – editor-in-chief, a position Mase would take on his junior year with much adieu. Next year was my turn, or so I thought.

As time went on, I focused more attention on this guy with wild curly hair – whip smart, witty with wordplay, deft with sarcasm. He was gentle, had a kind heart with a fondness and deep connection to music, which he manifested through the acoustic guitar he brought to college with him, along with all the Bob Dylan songs he knew by heart.

He was dating a gal at the time who was also in the journalism program at SMU. I remember she had her eyes on law school after graduation with her degree in journalism. She was smart, kind of sassy, and aggressive to boot. It was clear to me he was attracted to independent women with lots of brain power and quick comebacks.

In which case, I was made to order, and so began flirting a bit with Mase and he took notice, as did his girlfriend. Bottom line: he moved into my orbit and she moved on. We went to movies, smoked pot, drank beer, enjoyed parties with our Daily Campus comrades, did untold amounts of assignments for class, and made time for sex. He was a sweet lover, and back in the roaring 1970s that was a find. Men very often weren’t sexually in tune with what women wanted or needed. Many of them were still a bit Neanderthal and demanding, some were on the cutting edge of what it meant to be a sexual predator – dropping ruffies into a woman’s drink, which happened to me shortly before I took up with Mase.

It may have been the chastity belt joke about me floating among the boy students that provided the impetus for the invitation that hot day in mid-August when I returned to SMU for my junior year. By now I had a high profile on campus, what with my byline and accompanying stories showing up daily in the campus newspaper. But it was still curious to me when, out of the blue that day, a very handsome and polite young man with a manicured beard – who purported to be an SMU student whose mother was the dean of the Spanish Department – invited me to dinner. I said okay. I believe we first had a drink. While I’m not sure where, I’m conjuring it may have been when he dropped a ruffie into that drink of mine. After that, we got in his car and ostensibly were on the way to a restaurant when he said he wanted to show me an apartment he had just rented.

“Okay,” I said. I might have been wearing a sleeveless hip hugger dress – a bit darker than the color of Texas bluebonnets – that hit just above my knees. His impeccable manners had him gesturing for me to walk up a flight of stairs, then he followed me to a metal porch where I stood as he unlocked the door of the vacant apartment. It was carpeted in brown shag and consisted of a smallish living room adjacent to a galley kitchen, separated by a breakfast bar, the top formica splashed with gold specks. Wallpaper, stretched across one wall, was made up of large circles ringed in the color gold and filled with brown and orange. Very 1970s.

Then I remember him showing me around the tiny confines, opening a door and showing off a closet, and the next thing I knew, I was laying on the living room shag carpet on my back, a floppy doll, with him on top of me grunting and heaving. Don’t remember anything after that – not walking down the stairs from the apartment, not dinner, not a drive home, not getting into my bed. Nothing.

I only remember waking up in my apartment on my bed. Memories of that night had drifted away in my sleep. That day was registration for the upcoming fall semester classes. As I was getting dressed and ready to go, I realized there was not much I could do about the beard burn on my face, except hope the makeup tamped down the red rash on my cheeks and chin. Thank goodness the stinging carpet burns on my backside weren’t visible.

I don’t remember telling any of my friends. I just tried to pretend it didn’t happen. I was embarrassed and had no idea what to do or what it was I should do. All too often, us girls did not talk to each other about these occurrences – wary of being judged and of word spreading around campus. It was a strike against you, victim blaming all around, fueled by the patriarchy and its minions. At the time, that was often the dilemma of so many women and girls. I just hoped I didn’t get pregnant. It wasn’t long before I buried deep in my memory banks the experience of having a ruffie dropped into my drink by a predator groomed by the patriarchy.

I began looking forward, in particular to spring of that junior year. It signaled the time for the SMU Publishing Board to select the editor-in-chief for the following year. I had traveled the route to get to this spot. I knew I had earned it.

But hold your horses. Before I wrap up this story about my journey to become editor-in-chief of the Daily Campus, I’m moved to share its prelude, which took place during high school.

There was no newspaper at Salina High School, in Salina, Kansas, so I opted for a stint on the yearbook staff. My goal, of course, was to earn the position of editor, which would look good on my resume for college applications. My junior year in high school, I applied for the editor position but was told by the Mister who was the yearbook advisor that I wouldn’t get the position. Why? “Because you are a girl,” he explained in a calm voice.

“That’s not right,” my mother said when I told her what Mr. Advisor told me earlier that day. “I’m going to have a conversation with him.” The meeting came the following day. I was curious as to how this scene would fall out. It was not something I had seen my mother do much of, at least nothing this blatant. The meeting took place in the afternoon when the final bell rang and the halls had cleared. Mozelle was very determined in her walk. I could not keep up with her. Or perhaps I chose to walk behind her purposefully so I could take in her determination and fortitude.

We climbed a set of stairs to reach the yearbook classroom, a large room with a high ceiling, part of the gym, filled with sunlight and an array of desks and tables, different sizes of paper stacked against a wall on top of a bench. The room spoke to creativity. Time to cut to the chase after the niceties of introduction.

“I understand you told Kay she could not be the editor of the yearbook because she was a girl,” my mother stated.

“Yes, I did,” the advisor responded. “It’s school policy.”

“Is it written down somewhere?” The ping-pong conversation captivated my attention.

“Well, not exactly,” he said. “It’s just how it’s been for years.”

“What if Kay applied for the position?”

“Well, she can’t because she’s a girl and girls cannot be the editor of the Salina High School yearbook,” the advisor explained. “A girl can be assistant editor,” he added with a bit of a lilt in his voice.

On the way home, I told my mother that if assistant editor was as close as I could get, then I would take it. “You know what’s going to happen?”

“What?” she asked, knowing the answer all too well, since it had played out in her life many a time. Because that’s what happens to women and young girls.

“The boy who’s going to be the editor is not going to do any of the work. I’ll be doing it… and the skills I learn will come in handy,” I said with confidence and conviction. Besides, I didn’t mind having to put “assistant editor” on my college resume.

And, yes, I did do the boy editor’s job in addition to mine. The upside of this event in high school, I suspect, is that I had practice for when the scenario would replicate at SMU.

If it had not been for Mase, three other fellas on The Daily Campus newspaper staff, and a very supportive male Vice President of Student Affairs at SMU, I would have not had the editor-in-chief credential that served as the cherry on top of the resume that would launch my career in the professional leagues of journalism.

What would unfold was a great and grand example of the patriarchy at work on both sides of the fence, interestingly enough.

At the time of this little dust up, the student newspaper’s editor-in-chief was chosen for a year-long position, a long-standing “rule” of the SMU Publishing Board, an “independent” group that oversaw the newspaper. While I was clearly on a path to be appointed editor-in-chief – as I had satisfied every requirement needed – a roadblock cropped up. The Publishing Board was poised to give the job to a journalism major, who by his utter lack of journalistic talents, showed he was much more interested in the world of fraternity life. In the eyes of the would-be journalists at SMU who worked on the newspaper religiously for four years in order to get the cred and experiences needed to be a top-notch professional journalist, the idea of this fellow being awarded the position was anathema.

Along with Mase and the other fellows who were in my corner, I helped with the needed research and found that, around the country, most universities and colleges at the time had two editors during the year – one in the first semester and the other in second semester. The idea being, of course, to make that cherry-on-top of the resume available to twice as many budding journalists. This should be a no-brainer!

We took our research and went up the ladder – taking our claims and arguments to the Vice President for Student Affairs and returning shortly with a victory, thanks to my tenacity and my male comrades who were coming into adulthood with very different ideas of what women could, would, and should do. These guys were helping knock holes and gaps in the patriarchy. Butting heads with a Publishing Board that was gung ho to keep a woman out of the editor-in-chief position.

In May of ‘73, Mase and I both graduated along with many of our journalism comrades, and all of us went off to our various newspaper journalist jobs. Mase went to the Dallas Morning News, and I drove to Tennessee, where I had a reporter job waiting for me at the Memphis Commercial Appeal. We had talked about getting married, but I was set on working at a newspaper in the Deep South where legalized racial segregation, disenfranchisement, and discrimination had been a plague on Black folks for an interminable period of time. The time was ripe for change, what with the Civil Rights legislation signed into law in 1964 and followed one year later by the Voting Rights Act. These were the two most consequential pieces of civil rights law since Reconstruction, which followed the four-year Civil War that ended in 1865. While the racist Deep South suffered defeat, it continued – and continues to this day – to hold on to that racism.

At the time I went to Memphis, there was on-going tension around civil rights. The culture in southern states was in flux. I wanted to be part of the clarion call progressive newspapers in the south were making in support of laws paving the way towards equal rights for all people. But the scene I had dreamt of wasn’t a good fit. Turns out I didn’t have it in me to go out on my own, live by myself. I had barely been in Memphis two months when I decided to move back to Dallas. I was lonely for my friends and wanted to make sure I sealed the deal with my husband-to-be. It seemed important at the time, given the patriarchal indoctrination I had endured as a child and adolescent. I was to marry a man. So, figuring it would be a challenge to find another man like Mase, I felt compelled to get married promptly. Why might that be? Fear of the patriarchy. I did not want to get stuck with a man who seemed to be a good guy in the beginning but soon morphed into male entitlement. I knew Mase would not be that guy so I asked him to marry me. And he agreed. So much for my idea of living an independent life in a far-away-town doing journalism.

Our nuptial festivities took place in Dallas inside a chapel located on the SMU campus on a late October evening in 1973. During the marriage we both worked as journalists, did not commingle our money, enjoyed fun vacations, had good sex, and never got pregnant, the later being my saving grace. We divorced in 1979 as I was racing towards the closet door.

At the time, I still had my wedding dress. Now that I was out as a lesbian I felt free to ditch the dress – a construct of the patriarchy to keep women feminine. I sold it to a gay guy at a garage sale my friend held one Saturday. It was maybe a couple years later that I loaded up my car with every skirt and dress I owned and delivered the feminine clothing to yet another friend’s garage sale.

The tomboy in me wanted something more. They say clothes make the man. I say clothes make the butch, and that butch probably doesn’t cotton to feminine clothing. (What butch goes femme?) But, none of that makes the butch, a her, less of a woman.

If you are finding my work valuable, meaningful, or inspiring, I’d truly appreciate your support with a paid subscription or one-time donation. In gratitude.

Kay, great piece. You were part of an era.

Another banger of a piece, Kay! :D I adore reading about the US in the mid-late 20th century like this. :)